This past weekend the North Koreans tossed the old middle finger once again at the world and tested a nuclear device:

“Was it another fizzle?†asked Hans M. Kristensen, a nuclear expert at the Federation of American Scientists.

“We’ll have to wait for more analysis of the seismic data, but so far the early news media reports about a ‘Hiroshima-size’ nuclear explosion seem to be overblown.â€

(Illustration found here).

This relationship on the Korean peninsula is real peculiar.

Two physical countries: North and South.

And these two countries have been in a constant state of crisis, or near-crisis with each other for now-near 60 years.

Nothing real odd about the set-up on its face, down through human history there’s been a shitload of similar situations — bunch of peoples/nations antagonistic and bickering for long periods of time — but the strange lies in the lay of the land and a bad, bad doohickey/weapon.

In the South, the landscape is one of an highly-developed nation, a place teeming with iPods and laptops: South Korea is classified as a high-income economy by the World Bank and an advanced economy by the IMF and CIA. Its capital, Seoul, is a major global city and a leading international financial centre in Asia. South Koreans enjoy one of the highest living standards in the world and have a high life expectancy and a high level of economic freedom.

Despite that, or maybe because of that, South Korea has a national mental illness: Honor via suicide.

The suicide of former president Roh Moo-Hyun last week hightlighted the problem — The country has one of the highest suicide rates among economically-advanced countries, with rates of suicide doubling to 21.9 deaths per 100,000 people between 1996 and 2006.

These South Korean suicides, Roh included, are nothing but pantywaists — How would these guys react if instead they were citizens of a nation a few miles north of Seoul, that major global city, in a place seemingly which could exist only if Phillip K. Dick and George Orwell had collaborated on a horror tale.

In the North, the landscape is blighted by the blinding light reflecting off the face of the Great Leader Kim Il-sung, though dead for 15 years.

When he died, his number-one son, Kim Jong-il, took over with the daddy still the real head honcho, being the “Eternal President” forever — North Korea, officially called the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), is the most secretive society on earth, no one knows what really is going on in there as only about 2,000 Westerners a year are allowed inside.

And although the Great Leader instituted “juche” ideology, or national self-reliance in being “a revolutionary ideology with a people-centred view of the world that aims to realise the independence of the masses, the guiding principle of its actions,” the entire country is a hell-hole:

Aid agencies have estimated that up to two million people have died since the mid-1990s because of acute food shortages caused by natural disasters and economic mismanagement.

The country relies on foreign aid to feed millions of its people.

The totalitarian state also stands accused of systematic human rights abuses.

Reports of torture, public executions, slave labour, and forced abortions and infanticides in prison camps have emerged.

A US-based rights group has estimated that there are up to 200,000 political prisoners in North Korea.

North Korea is the most militarized country in the world having the fourth-largest with an estimated 1.1 million armed personnel and operates an enormous network of military facilities scattered around the country, a large weapons production basis and an extremely dense air defence system.

And along with uniformed military, the country also has what’s called the Worker-Peasant Red Guard, a reserve force comprising of between 3.5 and 4.7 million troops. (Source: Wikipedia).

North Korea is a late bloomer in the nuclear field — After George Jr. proclaimed the DPRK a member of the “Axis of Evil” in 2002, Kim II started a route that would take the country to its first nuclear test four years later.

All this despite some encouraging non-nuclear news in the 1990s, but all to no avail.Â

Which brings us to the DPRK’s nuclear and missle testing the past few days, a situation which has everybody ringing the alarm bells — especially Japan, a country living under the shadow of not only a possible missile strike from North Korea, but the Hiroshima/Nagasaki nightmare.

And recent events could bring about a re-arming of Japan — a first-strike ability using the old chestnut of a “pre-emptive strike” to take out a supposed danger.

Talk in Japan considers just that:

“North Korea poses a serious and realistic threat to Japan,†former defense chief Gen Nakatani said today in Tokyo at a meeting of Liberal Democratic Party officials.

“We must look at active missile defense such as attacking an enemy’s territory and bases.â€

Reports of North Korea’s test last weekend generally claimed the firepower produced was at or about that equal to the bombs used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki — an all-US event.

As Justin Raimondo mused at antiwar.com: “It is certainly not lost on the North Koreans that the U.S. could just as easily rationalize a similar attack on yet another nation of yellow-skinned people.”

Hiroshima is another word for infamy — ironic is FDR’s Pearl Harbor quote — and in the years since August 6, 1945, the city has been a focal point of anti-nuclear war.

A nation’s guilt, a world’s guilt of not only nuclear weapons, the terrors of war itself is epitomized by the dream/nightmare that is Hiroshima.

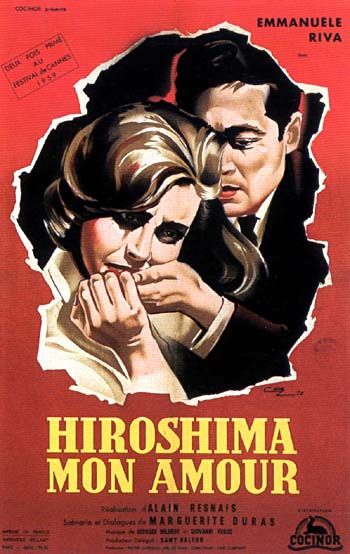

Into this dream/nightmare is a love affair wrapped around the horror of Hiroshima and the guilt of life in war — Frenchman Alain Resnais‘ “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” a 1959 film which gathers together war and memory in a stream-of-consciousness montage backgrounded by the city itself.

Into this dream/nightmare is a love affair wrapped around the horror of Hiroshima and the guilt of life in war — Frenchman Alain Resnais‘ “Hiroshima Mon Amour,” a 1959 film which gathers together war and memory in a stream-of-consciousness montage backgrounded by the city itself.

The opening sequence of shots — a series of naked shoulders and arms, upon which what at first appears as sweat, but is actually fine-grained radioactive dust — forces one to wonder at the true nightmares the bomb actually brought to the city’s population in August 1945.

From Marguerite Duras, the noted French writer who scripted the Resnais film:

“Thus the initial exchange is allegorical. In short, an operatic exchange. Impossible to talk about Hiroshima. All one can do is talk about the impossibility of talking about Hiroshima.”

(Illustration found here).

North Korea and Hiroshima: An impossibility to fathom.