In a sense within my own personal space, cocooned as it were in time, knowingly-conscious right now in the nowadays, a reflective mirror via Miss Emily Dickinson: “Wonder — Is Not Precisely Knowing”

In a sense within my own personal space, cocooned as it were in time, knowingly-conscious right now in the nowadays, a reflective mirror via Miss Emily Dickinson: “Wonder — Is Not Precisely Knowing”

Wonder—is not precisely Knowing

And not precisely Knowing not—

A beautiful but bleak condition

He has not lived who has not felt—Suspense—is his maturer Sister—

Whether Adult Delight is Pain

Or of itself a new misgiving—

This is the Gnat that mangles men—

An age of pure weird seemingly without knowledge of the fact — a SmartPhone-sliding loss of empathy in understanding the knowing.

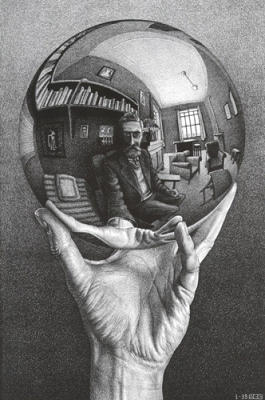

(Illustration: MC Escher’s ‘Three Spheres II,‘ found here).

Our age would be nearly-beyond the imagination just short decades ago — knowledge has seemingly mega-increased way-beyond knowing just ‘something.’ And one wonders at the knowing.

In knowing, ‘the hard problem’ is our brain.

A couple of weeks ago, I ran across a detailed piece at The Economist about human understanding:

“I THINK, therefore I am.”

René Descartes’ aphorism has become a cliché.

But it cuts to the core of perhaps the greatest question posed to science: what is consciousness?

The other phenomena described in this series of briefs — time and space, matter and energy, even life itself — look tractable.

They can be measured and objectified, and thus theorised about.

Consciousness, by contrast, is subjective.

As Descartes’ observation suggests, a conscious being knows he is conscious.

But he cannot know that any other being is.

Other apparently conscious individuals might be zombies programmed to behave as if they were conscious, without actually being so.

In reality, it is unlikely that even those who advance this proposition truly believe it, as far as their fellow humans are concerned.

Cross the species barrier, however, and matters become muddier.

Are chimpanzees conscious? Dogs? Codfish? Bees?

It is hard to know how to ask them the question in a meaningful way.

Problem isn’t the question, but the glitch in the answer is ourselves.

In a much-interesting, lengthy essay from last August by Nicholas Epley at Nautilus is an examination of interplay between us humans — conscious knowledge note:

This example illustrates what psychologists refer to as the curse of knowledge, another textbook example of the lens problem.

Knowledge is a curse because once you have it, you can’t imagine what it’s like not to possess it.

You’ve seen other people cursed many times.

For instance, while on vacation, have you ever tried to get driving directions from a local?

Or talked to an IT person who can’t explain how to operate your computer without using impenetrable computer science jargon?

In one experiment, expert cell phone users predicted it would take a novice, on average, only thirteen minutes to learn how to use a new cell phone.

It actually took novices, on average, 32 minutes.

The lens of expertise works like a microscope, allowing you to notice subtle details that a novice might not catch but also sharpening your focus in a way that can allow you to miss the bigger picture and make it difficult to understand a novice’s perspective.

Trying to correct this lens first requires becoming aware of its influence.

The problem is that it’s hard to know when you are being affected by your own expertise and when you are not…

(h/t The Big Picture).

And to correct our ‘consciousness‘ from ourselves, we can interplay with the baser animals.

A paper published last week from MDPI (Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute), based in Basel, Switzerland, and titled, ‘“Chickens Are a Lot Smarter than I Originally Thought” — Changes in Student Attitudes to Chickens Following a Chicken Training Class,’ reveals a ‘practical class’ for fowl knowledge.

From the abstract:

In the post-versus-pre-surveys, students agreed more that chickens are easy to teach tricks to, are intelligent, and have individual personalities and disagreed more that they are difficult to train and are slow learners.

Following the class, they were more likely to believe chickens experience boredom, frustration and happiness.

Females rated the intelligence and ability to experience affective states in chickens more highly than males, although there were shifts in attitude in both genders.

This study demonstrated shifts in attitudes following a practical class teaching clicker training in chickens.

Similar practical classes may provide an effective method of teaching animal training skills and promoting more positive attitudes to animals.

A chicken thinks, therefore it is…until it’s KFC.