Last night on CBS News, an interview with US Defense head Leon Panetta took place on what’s called “the doomsday plane,” a modified Boeing 747, termed an E-4B by the miltary, and tricked out with a shitload of science-fiction-sounding gear to aid in evading a Judgment-Day scenario.

Last night on CBS News, an interview with US Defense head Leon Panetta took place on what’s called “the doomsday plane,” a modified Boeing 747, termed an E-4B by the miltary, and tricked out with a shitload of science-fiction-sounding gear to aid in evading a Judgment-Day scenario.

Panetta’s blubberings as usual were nonsensical, but the aircraft was what peaked an interest.

When bad shit hits the fan — even a zombie apocalypse — the president, military types and other important folks will be saved to carry on while the rest of us run for the burning hills: The $223 million aircraft is outfitted with an electromagnetic pulse shield to protect its 165,000 pounds of advanced electronics. Thermo-radiation shields also protect the plane in the event of a nuclear strike.

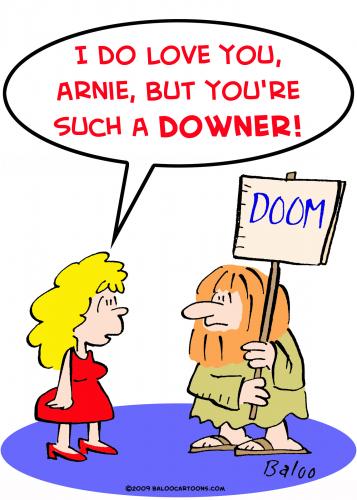

Nice ride in an era of gloomy doom-speak.

(Illustration found here).

Scary is the events unfolding now in North Korea — even as everybody on the planet have their panties in a bind over Iran’s so-called nuclear ambitions, another way-more serious situation lies via Pyongyang — and the fright is the secrecy.

Kim Jong-il kicked the bucket without anybody outside a few North Koreans knowing about it, and all despite billions of dollars worth of all kinds of high-tech gear.

From the New York Times:

For South Korean and American intelligence services to have failed to pick up any clues to this momentous development — panicked phone calls between government officials, say, or soldiers massing around Mr. Kim’s train — attests to the secretive nature of North Korea, a country not only at odds with most of the world but also sealed off from it in a way that defies spies or satellites.

Asian and American intelligence services have failed before to pick up significant developments in North Korea.

Pyongyang built a sprawling plant to enrich uranium that went undetected for about a year and a half until North Korean officials showed it off in late 2010 to an American nuclear scientist.

The North also helped build a complete nuclear reactor in Syria without tipping off Western intelligence.

…

“ ‘Oh, my God!’ was the first word that came to my mind when I saw the North Korean anchorwoman’s black dress and mournful look,†said a government official who monitored the North Korean announcement.

What bullshit — the Korean peninsula is a tender box waiting for a match while the rest of the world sits in the dark.

The Washington Post: “It is scary how little we really know,†said one administration official who closely follows the region and who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive intelligence. “I don’t think you can overstate the concern.â€

When one takes a truthful view of the world nowadays, there’s much to be alarmed about and gloomy, but it’s only a respite before the doom arrives, and it will.

According to all the data, we (the planet) can’t avoid a coming horror — between climate change, energy depletion, worldwide financial collapse, and just plain old war, amongst a host of lesser calamities — although apparently the world sits willingly in the dark.

Last weekend, the UK’s The Guardian ran a detailed piece on this age of destruction — titled, “The news is terrible. Is the world really doomed?” — and presented all the gloomy evidence to support a coming implosion/explosion of civilization.

A few key points:

“The apocalypse,” wrote the German poet and essayist Hans Magnus Enzensberger in 1978, “is aphrodisiac, nightmare, a commodity like any other … warning finger and scientific forecast … rallying cry … superstition … a joke … an incessant production of our fantasy … one of the oldest ideas of the human species.

Its periodic ebb and flow … has accompanied utopian thought like a shadow.”

…

This autumn, as the estimated world population passed seven billion, an earlier prophet of doom, Paul Ehrlich, co-author of the 60s and 70s bestseller The Population Bomb and professor of population studies at Stanford University in California, resurfaced in the British press to warn that demand for the planet’s resources would soon decisively exceed supply.

“Civilisations,” he reminded this newspaper, “have collapsed before.”

…

In July, the word “apocalypse” appeared 60 times in British national newspapers.

In August, 70 times.

In September, 92 times.

In November, 100 times.

Usually calm Guardian columnists have started to ponder armageddon.

After the chancellor George Osborne’s bleak autumn statement on the economy, Zoe Williams discussed the pros and cons of food hoarding.

In November, Simon Jenkins declared: “Today’s [economic and political] predicament is unquestionably worse than the 1970s.”

The same month, Ian Jack wrote: “Build a bunker with a vegetable plot on some high ground and leave it to your grandchildren: dangerous levels of climate change now look all but inevitable.”

…

Meanwhile, for westerners who instinctively look to other countries or big political ideas for inspiration, the possibilities seem to be withering.

The US appears economically declining and politically dysfunctional.

The EU is damaged and possibly disintegrating.

The social democracy of Europe’s postwar golden decades seems unable to modernise itself.

The ability of Thatcherism and its international variants and descendants to rescue countries from national decline — if that ability ever truly existed — seems to have run its course.

Žižek argues that over the past five years the west has suffered a form of bereavement.

To describe the resulting mindset, he uses the famous “five stages of grief” model devised in 1969 by the Swiss-American psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

The current combination of public doominess and desperate-looking political summits certainly seems to feature the middle three.

Gray sums up the prevailing mood more succinctly: “People are afraid – for good, practical, experientially based reasons.”

The entire post covers all the ugly angles.

A nagging truth, however, is there’s not much the average-guy-on-the-street can do about it.

As I sit here in the comfort of my apartment on a clear, pre-dawn morning, the world outside is quiet and still — I can hear the slight roar of the Pacific Ocean — and the coming horror seems so far remote and so Horn of Africa.

Time is a much flexible measure, although time never changes, slows or changes direction.

A downer indeed if one doesn’t have the ears to hear.