(Illustration: ‘Redhope‘, street art by Shepard Fairey, and found here).

(Illustration: ‘Redhope‘, street art by Shepard Fairey, and found here).

Just paying attention to what’s going on around you nowadays is a way-depressing and emotional bowel-suck of an endeavor, and if you’re a ‘news nut‘ (vs a ‘news addict,’ which is really just more druggie-like than the perceived institutional-grade crazy) doomscrolling through the activities of a freaked-out worldwide society of scared, insane everybody and everyone — shit is indeed worse than you figured, and actually, life is really condensed down into the metaphor of the frog in a hyper-boiling pot of water.

We’ve known the water was warming for a while, but ignored the faint pain through deceptive ignorance, and now it’s starting to really, really hurt. And we can tell the suffering is only going to get worse. The big problem is it might be too late to try and crawl out of the pot.

On top of all the political and medical-health bad shit flowing around, climate change poses a much bigger, a more-disasterous explosion, and creates a tendency to underplay the time element on the plotline of global warming’s impact on humanity’s life on this our one-and-only planet.

The last couple of days, I’ve seen and posted about the jolt on science and catastrophe from off the new satirical film, “Don’t Look Up,” as a precursor to the dangerous effects coming from climate change, though, the movie’s interest is a coming runaway comet heading to earth. Time is crucial and is taken for granted.

In a new appraisal today at Scientific American, the same ho-hum sense of plenty of time for climate change, and yawn, mankind will survive trope. Although the reviewer, Rebecca Oppenheimer, curator and professor of astrophysics at the American Museum of Natural History, gives a high-five for the science and the values of “Don’t Look Up,” she brushes off the real horror of our environmental calamity:

Global warming is a different beast than a “planet-killer” comet. The timescale for a catastrophic comet impact is short, perhaps as short as six months, more likely a few years.

Global warming does not provide a date six months or 600 years from now when the last human being on Earth will die.

Indeed, it is unlikely to wipe out all life, given life’s 3.5-billion-year history spanning massive changes in temperature and atmospheric chemistry.

Go read the whole review, she gives it a hearty thumbs-up and proclaims it funny, touching and a movie landmark: ‘At last, mainstream Hollywood is taking on the gargantuan task of combatting the rampant denial of scientific research and facts.‘

However, people seem to view climate change in that tomorrow is tomorrow, wait and assess it then category, which is an injustice to the speed of time, once it’s close at hand. Yet it’s coming fast and is already here and the killing fields of rising temperatures is not that far away — might be closer than we even suppose:

We MUST stand up and save our planet Earth ??#climatechange #ClimateAction #netzero #ClimateCrisis #COP26 #COP27 #nature #SDGs #trees #savetheplanet #TogetherForOurPlanet pic.twitter.com/n8IBQJRKPa

— COP27? (@COP27_Egypt) December 26, 2021

Climate change can be easy or it can be hard. Time, however, is not waiting for history.

Chris Begley, a maritime archaeologist and author of, “The Next Apocalypse: The Art and Science of Survival,” tackles the ‘a‘ word — apocalypse — in an op/ed at The Washington Post this morning, and despite some expert historical takes on civilized ‘collapses,’ seems to miss the urgency:

I am an archaeologist, and like many archaeologists, I study societies that no longer exist. All societies fall apart. Ours will, and that process may have already begun. We see the signs in the weather, in the pandemic and in supply chain disruptions.

We worry about a collapse, but we also fantasize about it in the post-apocalyptic stories we create. These fantasies represent our fears, but also our desires.

Even in destruction, the next apocalypse represents a chance to start over, perhaps even a welcome simplification of our cluttered and increasingly complex contemporary reality.The problem is that when we think in these terms, imagining life after the end, we inevitably prepare for the wrong disaster. Archaeology shows us that when real societies fall apart, their demise is nothing like our anticipatory pre- and post-apocalyptic fictions.

The stories we imagine matter. They set the parameters for our response and shape the way the future unfolds. We are imagining a future that will not happen, and the consequences could be catastrophic.Begley notes the ability of people to survive in all previous ‘collapses,’ and the time it takes for that ‘collapse‘ to actually take place, although an ELE (extinction-level event) appears not to have been figured into the scenario — climate change is an ELE if allowed to play out to the grueling end.

Our predicament is cast as standard history and not a way-unusual, unique situation as the poor are smacked first, but the rich can only just put off the inevitable for so long — the rising heat will eventually get everybody and most of the planet will become uninhabitable:Apocalyptic narratives also mislead us about the speed of societal declines. Except for something like a volcanic eruption, the stresses that lead to a dramatic change develop over a long time before things truly fall apart. If the proceedings are gradual enough, we might only identify the change as a “collapse” in retrospect.

This is not to say that these changes are not significant, even dramatic; in fact, changes at the end may accelerate so that the collapse seems sudden if you were not paying attention.

Usually, the decline happens over decades, even centuries, as was the case with the decline of the Western Roman Empire.

Even in cases of natural disasters, we see that our history and our response determine the degree to which a phenomenon becomes a disaster.

Some societies weather these events well, while poverty of limited resources exacerbate the suffering in others.The dramatic changes that we will face have deep roots that extend far into our past, and any solution will have to address that long history.

The coronavirus pandemic, for instance, has its roots in the destruction of animal habitats, in inequitable health-care systems and in decades of political strategies that polarized the population to the point where public health issues become political.

Instead of looking for causes and solutions that take into account that long buildup, we focus on the obvious and dramatic changes that occur when this lengthy process reaches a critical point.

We see this in our response to climate change. The decades of carbon emissions are less recognizable as a threat than the dangerous extraplanetary objects heading for Earth in narratives such as “Lucifer’s Hammer” or “Armageddon.” Like the apocryphal story of the frogs in the slowly heating pot of water, we notice the danger only when the water is nearly boiling and it might be too late.

Concluding in optimism: ‘This might be the most important lesson for the future: Like people in the past, we will persevere as a community. Survival will involve working together, doing the hard and messy work of cooperating, to create something new, maybe something better.‘

Hope is good, but reality makes that scenario unworkable. This is observable in current events, humankind cannot seem to cooperate with one another on a large-number of levels.

In don’t look in any direction — an explanation:

Here we are, once again…

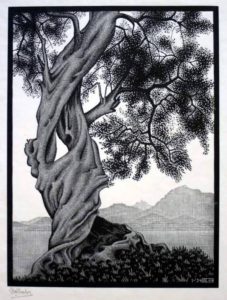

(Illustration out front: MC Escher’s ‘Old Olive Tree, Corsica‘ (1934). and found here).

(Illustration out front: MC Escher’s ‘Old Olive Tree, Corsica‘ (1934). and found here).