One thing is certain in history: Weapons of war have become more advanced as a civilization seemingly progresses, always and continually getting more bang for the buck, and in turn, becoming less humane, more indiscriminate in the killing.

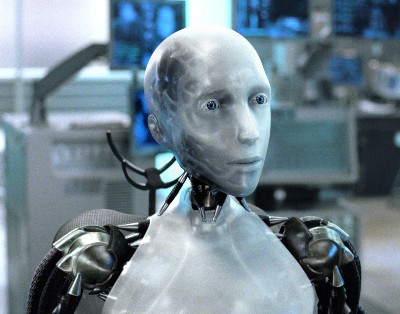

Modern war machines attempt to eliminate the human element altogether.

(Illustration of a two-man Gaelic battle chariot found here).

Even in the Stone Age, getting stoned acquired technology:

- A widespread early weapon, perhaps finally understood, is the “stone handaxe.”

This is a flat, sharp-sided stone disc, with an egg-shaped or triangular projection.

Some paleontologists built one and threw it, and noticed that it lands with the pointed edge digging into the ground.

They believe that it could be a “killer frisbee” to harvest animals from a tightly packed wild herd.

And as hunters became a collection of warriors bent on battle against other humans, war machines were directed from animal life to ending other human lives.

When much younger, I held a kind of uncomprehending fascination with war machines — not the national kind of war machine of armies, navies and whatnot, but machines as weapons — ancient Mesopotamian chariots, medieval siege weapons, WWI tanks, even minutely down to the SdKfz 250 halftrack, a German multi-purpose WWII vehicle.

Now there’s a vivid, emotional understanding these weapons produce horror beyond comprehension, and war, especially war in just the last 100 years or so, has become a grisly, collateral-damaging piece of work — Visually witness carnage produced down range from cannon firing in the 1977 film, A Bridge Too Far; the safe and easy, informal precision of those working the guns versus the ear-shattering, body-slaughtering nightmare far away, the end result of those fascinating war machines.

However, slaughter ain’t simple and cheap in the modern age.

Despite dealing with what could be a $1 trillion dollar US defense budget, Chalmers Johnson noted in another thought-provoking, though disheartening, piece at TomDispatch, the US military “...seems increasingly ill-adapted to the types of wars that Pentagon strategists agree the United States is most likely to fight in the future, and is, in fact, already fighting in Afghanistan — insurgencies led by non-state actors.”

And President Obama is working to cut the DOD budget by 10 percent, but the generals will be fighting tooth and F-22 to keep the cash flowing.

One budget item to remain, however, and one to probably even get an extra financial kick, is the hugely successful “the unblinking eye” — unmanned aerial drones, UAVs.

In fact, last month, from DefenseLink:

In fact, last month, from DefenseLink:

- “Next year, the US Air Force will procure more unmanned aircraft than manned aircraft,” Air Force Lt. Gen. Norman Seip, commander of Twelfth Air Force (Air Forces Southern) said.

And from a report last year from the Teal Group, an aerospace and defense market analysis firm, that UAV spending will more than double over the next decade to $7.3 billion, totaling close to $55 billion in the next ten years.

The US, of course, will account to 73 percent of worldwide spending on UAVs, with most of it going to the military.

(Illustration found here).

- “The most significant catalyst to this market has been the enormous

growth of interest in UAVs by the US military, tied to the general trend

toward information warfare and net-centric systems,” said Teal senior

analyst Steve Zaloga, one of the authors of the new study.

“UAVs are a key element in the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) portion of this revolution, and they are expanding into other missions as well with the advent of hunter-killer UAVs.”

Robots a-coming, hunter-killer robots, robots for war.

An interesting interview on these techno-marvels, warbots, was today at the Danger Room blog at Wired with P.W.Singer, a leading expert on modern warfare.

Singer, author of Wired for War, a look at science fiction turning into science reality on the battlefield, believes these unmanned war machines are part of the biggest break through in fighting since way back when.

- Our new unmanned systems don’t just affect the “how” of war-fighting, but are starting to change the “who” of the fighting at the most fundamental level.

That is, every previous revolution in war was about weapons that could shoot quicker, further, or had a bigger boom.

That is certainly happening with robots, but it is also reshaping the identity and experience of war. Humankind is starting to lose its 5,000-year-old monopoly of the fighting war.

And in five years:

- What we need to remember is that these are just the first generation, the Model T Fords compared to what is already in the prototype stage.

…

My sense is that we are going to see both a growth and widening in the use of robotics.

That is, you will have greater and greater use in areas where robots have already shown their capabilities (surveillance would be a great example) and more and more new areas that robotics will move into (think medbots).

This will be the case at land, in the air, more and more at sea and, of course, in space, where systems have to be robotic almost by definition.

And on the “emotional intelligence” on these warbots:

- I thought one scientist put it well: “My job will be eliminated before my hairdresser’s will.”

He may have a Ph.D. and carry out cutting-edge scientific research, but he can see the day looming at which machines may do that better.

Compared to a scientist, a hairdresser may be considered a lesser-skilled profession (Jonathan Antin excepted).

The reality is that [they] have to cut hair with an eye towards not merely precision, but also fashion and aesthetics. Plus, the customer has to trust them with a sharp blade near their eyes, ears and throat.

It is hard enough for me to trust the drones at Supercuts, even more of a leap of faith with a barber made at Spacely Sprockets.

Time will tell, and if history is any indication, these sterile, unmanned war machines will be even more horrifying that any kind of killer frisbees.