Overcast again this Tuesday afternoon, though, clouds appear to be thinning out some, so maybe we could get some real sunshine before dark.

Overcast again this Tuesday afternoon, though, clouds appear to be thinning out some, so maybe we could get some real sunshine before dark.

And appears, too, we might get some rain on Friday, and hopefully on Saturday as well — the rain was originally forecast for Saturday, but as usual, the score has moved up a day.

Any rain is good rain.

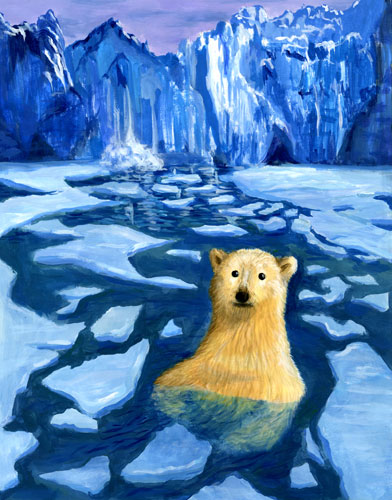

In the arena of the environment, significant news this week comes from Greenland, which has been kind of quiet of late, with a huge chunk of a glacier broke free in just two days (via The Weather Channel): ‘A massive chunk of ice that scientists say is roughly the size of Manhattan has broken off Greenland’s Jakobshavn Isbrae Glacier and begun floating into the sea, in what is likely one of the biggest ice calving events in recorded human history.’

(Illustration found here).

This big event supposedly happened over just two days — more from NASA:

These images were acquired 16 days apart in August 2015 by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) on the Landsat 8 satellite.

The top image shows the position of the glacier’s front on August 16, after the ice calved; the bottom image shows the glacier on July 31, before the event.

Turn on the image comparison tool see the difference in position of the glacier’s calving front.

“The calving events of Jakobshavn are becoming more spectacular with time, and I am in awe with the calving speed and retreat rate of this glacier,” said Eric Rignot, a glaciologist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“These images are a very good example of the changes taking place in Greenland.”

Other satellite images posted on the Arctic sea ice blog show that the ice broke off sometime between August 14 and August 16.

Some observers have speculated that the area of ice lost could be the largest on record.

However, these estimates are preliminary, and satellite images from before and after an event cannot show whether the ice was lost all at once, or in a series of smaller events.

“What is important is that the ice front, or calving front, keeps retreating inland at galloping speeds,” Rignot said.

According to University of Washington glaciologist Ian Joughin, the end of every summer for the last several years has seen Jakobshavn’s calving front move about 600 meters (2,000 feet) farther inland than the summer before.

Climate change is heavy on the ice — from Jason E. Box, professor in Glaciology, Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, at HuffPost earlier this month:

Indeed, ocean warming is arguably the climate change story.

The planetary energy imbalance due to the enhanced greenhouse effect is loading far more heat into the oceans than the atmosphere or land.

The world is 70 percent ocean-covered after all.

While there were signs of a warming hiatus in air temperatures from 1998 to 2012, the ocean continued to heat up, an equivalent of four Hiroshima bombs, per second, all day, every day.

The increase is continuing as we load the atmosphere with CO2.

The fundamental climate heating issue is a problem of too much of a good thing.

The natural greenhouse effect — a good thing — keeps temperatures tolerable at night.

But it has been enhanced by more than a century of people externalizing the environmental costs of stupendous economic growth, loading the atmosphere now with 42 percent more carbon dioxide, 240 percent more methane, 20 percent more nitrous oxide, 42 percent more tropospheric ozone, etc.

We have far too much gaseous carbon compounds now in our atmosphere, people.

The carbon pollution is, by the way, making our oceans too acidic, threatening the base of the marine food chain.

Would someone step forward and deny the changing ocean chemistry?

…

Seemingly the biggest issue with abrupt sea level rise comes from the now unstoppable loss of key sectors of west Antarctic ice and the discovery of more marine instability than we thought elsewhere.

Like glaciers thinning rapidly in east Antarctica.

Or in Greenland where improved bedrock maps reveal a marine connection an average of 40 kilometers further inland than previously thought.

Or like how new fjord underwater mapping reveals greater fjord depths, increasing the odds that deep warm ocean water can communicate with more Greenland glaciers than previously thought.

Surprise, surprise, surprise.

If the past decade of scientific inquiry is any indication, I’d say we are in for more surprises.

That notion is further supported by the fact that climate models used to project future temperatures lack key processes that likely reinforce warming or the effects of warming, not regulate it.

Ice flows easy…