Sprinkling-drizzle this mid-morning Thursday on California’s north coast, made wetter by some gusty winds — the NWS weather-thingy recorded gusts up to 41-mph before sunrise.

Sprinkling-drizzle this mid-morning Thursday on California’s north coast, made wetter by some gusty winds — the NWS weather-thingy recorded gusts up to 41-mph before sunrise.

After a somewhat-calm period earlier, seems the winds are kicking back in — a decent sized storm due tomorrow.

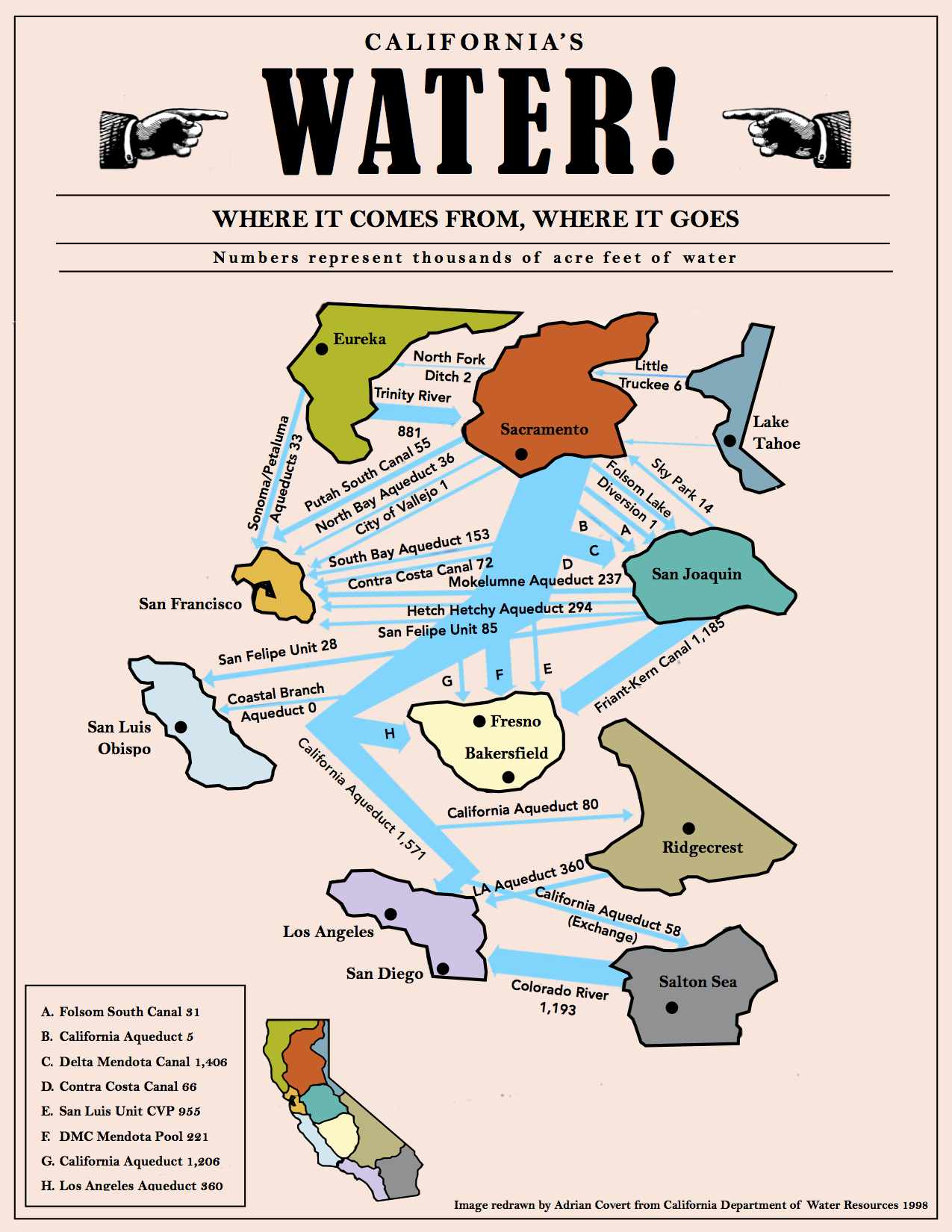

Once again, California’s top story is still weather related, but a contrary — way-loads of precipitation vs drought-dry. Now it’s rain-swollen everything, especially the impact on our state’s water system.

In light of the current Lake Oroville crisis, this simple illustration from Jeffrey Mount, former director of the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences (LA Times): ‘“You got this big bathtub — water doesn’t flow out of it very quickly.”‘

Yet the spigot won’t close…

Repairs to Oroville damn continue, though, matters are complicated by forecasts of the arrival by Monday of another one of those rain-marvels this season, an ‘atmospheric river,’ which as we all now know can produce some heavy rain, subject of the spigot analogy.

Oroville is not the only California reservoir in danger of overflowing — about a dozen, from Trinity Lake to Pine Flat, some experiencing record totals — and reportedly,, about half of the state’s 1,585 dams ‘have high-hazard potential.’

Our water system can be fragile, considering the importance of drinking water to the life of humans — further from the Times this morning:

Sixteen reservoirs, ranging from small to the biggest in the state, were above 90-percent full as of Wednesday morning.

Among them is the Don Pedro Reservoir, the sixth-largest in California and located near Yosemite National Park.

As of Wednesday afternoon, it stood at an elevation of 827.4 feet, just shy of its 830-foot capacity, the Turlock Irrigation District said in a statement.

The district continued to make releases to the Tuolumne River, which flows through Stanislaus County and into urban centers such as Modesto.

Forecasters predict about 4.7 inches of precipitation could fall in the watershed over the next six days.

Although the irrigation district said it does not anticipate an overflow, it advised residents of Stanislaus and Merced counties to register for emergency notifications.

In the Sacramento Valley, Shasta Dam, the spigot for California’s largest water storage lake, and Keswick Dam both released large volumes of water for multiple days into the Sacramento River.

The National Weather Service’s California Nevada River Forecast Center warns that the San Joaquin River at Vernalis in San Joaquin County will surge into the “danger stage” this weekend, the first time this winter that the center has made such a warning.

That could put the town of Lathrop, south of Stockton, at risk.

Earlier this week, evacuation orders were issued for Tyler Island, a small farming tract in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, after a compromised levee posed a risk of flooding.

To water experts, it’s a pattern that plays out in years of heavy rains.

Lakes pushed to capacity have placed tremendous strain on levees, some of which were built long ago and were weakly constructed. Perceived as fail-safes, experts say levees were meant to reduce the frequency of floods, not stop them altogether.

“They’re really the No. 1 defense against floods, and they’re not very good at it,” Mount said.

“Levees are kind of unreliable partners in flood management.”

Another weather-related feature, this concerning our coastlines — seems the slow-witted, somewhat dry El Niño of way-last year did leave a mark.

In a new study, US west coastal erosion was found to be 76-percent above the normal for winter shoreline retreat, so shows data off the 2015/16 El Niño event.

From ResearchGate.net yesterday, and one of the researchers, Dr. Patrick L. Barnard, of the US Geological Survey:

Beaches may not recover for years.

Most shorelines were still 10-20 meters more eroded in the fall of 2016 than in fall 2015, prior to the winter storm season.

This leaves coastal communities more vulnerable to future storms, including a greater risk of flooding and infrastructure damages due to narrower beaches.

Sand was transported far offshore, in some cases lost from the littoral system, but also observed abandoned in surf zone bars that haven’t yet migrated back to shore.

For California, the multi-year drought, which limited sand production from coastal watersheds, leading up to an exceptionally dry El Niño with extreme wave conditions, is the worst-case scenario for coastal erosion.

But this is a scenario that is likely to become more common in the future due to projected climate trends, which will be exacerbated by accelerating sea level rise.

And climate change with a full tub…

(Illustration above: ‘California Water Map,’ found here).