Rain and gusty wind this late Wednesday afternoon on California’s north coast as we continue with a wet-weather season that just don’t want to end.

Rain and gusty wind this late Wednesday afternoon on California’s north coast as we continue with a wet-weather season that just don’t want to end.

Reportedly, next decent break is maybe Saturday afternoon — all rain and wind until then.

Indeed, this has been a water-water season — Gov. Jerry Brown last week declared the drought over except for some counties in the central valley, and a snap dry-to-wet motion (LA Times): ‘“The dry periods are drier and the wet periods are wetter,” said Jeffrey Mount, a water expert and senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California.

“That is consistent with what the climate simulations are suggesting would be a consequence for California under a warming planet.”‘

Just a year ago, we were in record dry, and in a whiplash, more water…

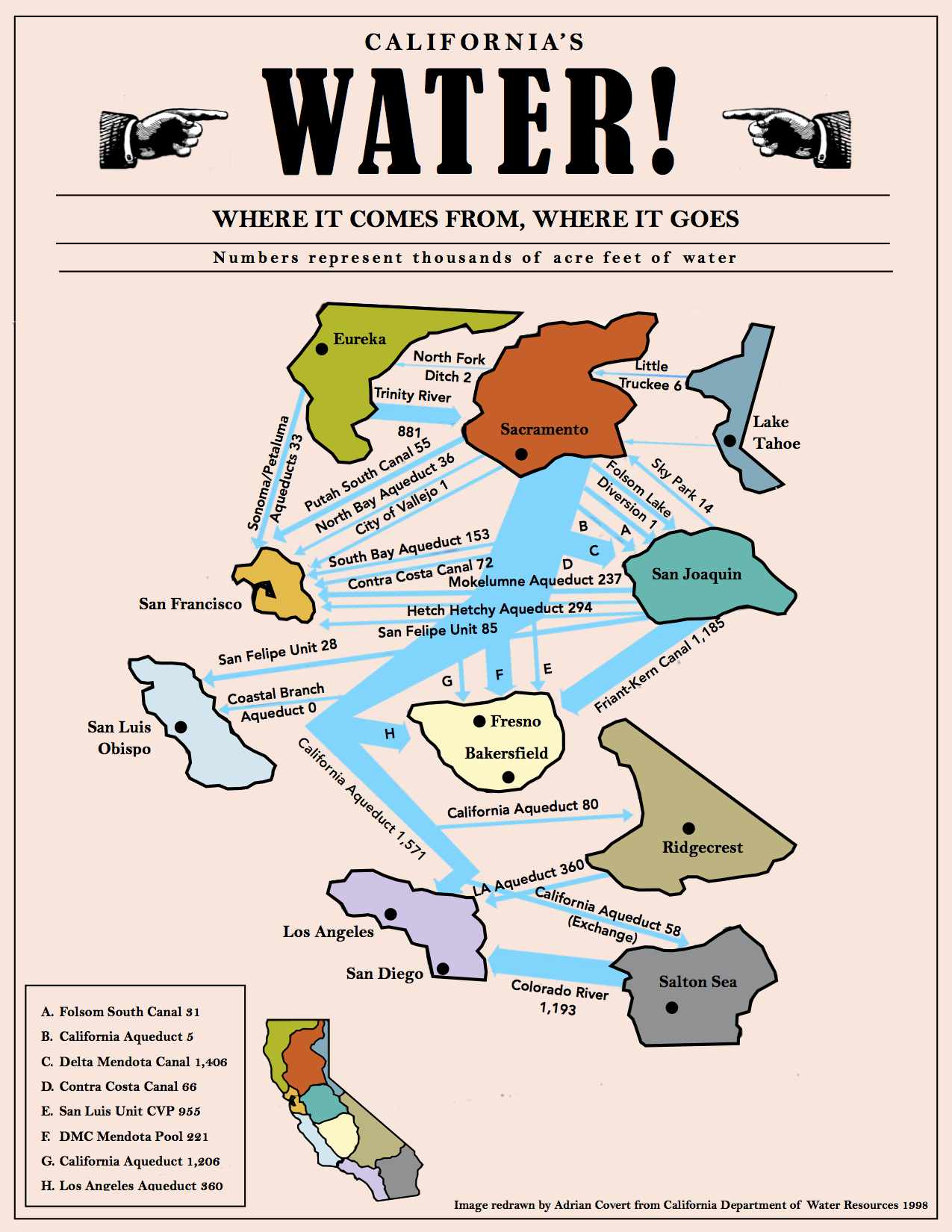

(Illustration above: ‘California Water Map,’ found here).

The government may decide the drought is over, but scientists look hard at the situation with a skeptical eye — Dr. Eugene R. Wahl with the NOAA: ‘“The odds of the state completely recovering from its extreme dryness within two years are estimated at less than 1 percent.”‘

On top of rainwater, below in underground water that accumulates over millennia in aquifers — is vanishing at an “alarming” rate.

So, there’s that, too…

Further from the LA Times:

Warming global temperatures can have a profound effect on weather patterns across the planet.

Changing the distribution of warmth in the ocean drives changes in the atmosphere, which ultimately decides how much precipitation gets to California, Mount said.

Warm weather worsened the most recent five-year drought, which included the driest four-year period on record in terms of statewide precipitation.

California’s first-, second- and third-hottest years on record, in terms of statewide average temperatures, were 2014, 2015 and 2016. And it’s no coincidence that California’s extreme water supply woes coincided with hot weather.

Warm temperatures in 2015 made the precipitation that did fall drop as rain instead of snow.

Some rain that fell in the early part of that winter had to be flushed out to sea to keep space available in reservoirs just in case flooding came later.

By spring 2015, the Sierra and Cascades produced a dubious historical record — the smallest snowpack on record, just 5-percent of average.

And this winter’s near disaster at the overflowing Lake Oroville was in part caused by warm storms too.

Exceptional water flows into the state’s second-largest reservoir came not only from a constant stream of “atmospheric river” storms that happened to strike California but also because so much precipitation was coming down as warmer rain.

Colder snow would not have posed an immediate flood risk.

A new study from the NOAA reports it could be decades until the drought is whipped for good:

Between October 2011 and September 2015, California saw its driest four-year period in the instrumental record, which dates back to 1895. ‘

Parts of the state lost more than two full years of precipitation during the prolonged, severe dry spell. ‘

But, a new study by NOAA NCEI scientists (link is external) suggests that from the longer-term view of paleoclimate records, the southern Central Valley and South Coast parts of the state saw their worst dry spell in nearly 450 years.

Published in the Journal of Climate (link is external), this study also looked at how long it would take the state to recover from its current precipitation deficits.

And, the scientists found that California’s hardest hit areas would likely need several decades for their long-term average precipitation to recover back to normal levels, starting from the 2012–2015 deficits.

“The odds of the state completely recovering from its extreme dryness within two years are estimated at less than 1 percent,” said Dr. Eugene R. Wahl, NCEI paleoclimatologist and lead author of the study.

“But, that may be what’s happening right now if very wet conditions continue into spring.”

…

In a warming world, higher temperatures could combine with and amplify severe precipitation deficits.

If temperatures continue to rise as they have, the U.S. Southwest could be facing “megadroughts” (link is external) — worse than any droughts in the region since medieval times — by the second half of the 21st century.

Rain, rain until the dry is not dry…