Another strange little twist in modern living.

From the BBC this week:

From the BBC this week:

The observations are baffling astronomers, who are due to study new pictures of the Sun, taken from space, at the UK National Astronomy Meeting.

The Sun normally undergoes an 11-year cycle of activity. At its peak, it has a tumultuous boiling atmosphere that spits out flares and planet-sized chunks of super-hot gas. This is followed by a calmer period.

Last year, it was expected that it would have been hotting up after a quiet spell. But instead it hit a 50-year low in solar wind pressure, a 55-year low in radio emissions, and a 100-year low in sunspot activity.

(Illustration found here).

Of course, this little wrinkle can’t be blamed on CO2, global warning, greenhouse gases, etc.

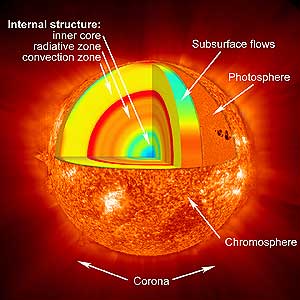

In the vast reach of the sun, the earth is just a toy — Energy generated in the sun’s core takes a million years to reach its surface.

Every second 700 million tons of hydrogen are converted into helium ashes.

In the process 5 million tons of pure energy is released; therefore, as time goes on the sun is becoming lighter.

But of no help to us.

From the BBC story:

In the mid-17th Century, a quiet spell – known as the Maunder Minimum – lasted 70 years, and led to a “mini ice age”.

This has resulted in some people suggesting that a similar cooling might offset the impact of climate change.

According to Prof Mike Lockwood of Southampton University, this view is too simplistic.

“I wish the Sun was coming to our aid but, unfortunately, the data shows that is not the case,” he said.

…

“If you look carefully at the observations, it’s pretty clear that the underlying level of the Sun peaked at about 1985 and what we are seeing is a continuation of a downward trend (in solar activity) that’s been going on for a couple of decades.

“If the Sun’s dimming were to have a cooling effect, we’d have seen it by now.”

Just as massive fires are currently burning out of control in South Carolina, a new study suggests these kinds of fires, more seen the last few years, especially in the drought-soaked western US, are fueling global warming:

Carbon emissions from deforestation fires have a significant impact on global warming, according to an international study.

The study, which appears in today’s edition of Science, provides the first consensus on the affect of fires on climate change.

“Fire has been underestimated as a contributor to climate change,” says study lead author Professor David Bowman of the University of Tasmania.

“In the past it was thought that fires were a steady state.”

Bowman says scientists have assumed that the carbon released into the atmosphere from burning plants, was equivalent to the carbon reabsorbed when plants regrow.

But the study’s authors note a marked reduction in fire events since 1870, which they speculate may be the result of intense farming and grazing, along with negative attitudes towards fire.

As a result, says Bowman, increased fuel loads and climate change has resulted in more intense deforestation fires. These fires release more carbon into the atmosphere, place increased stress on forest recovery, and result in less carbon being sequestered from the atmosphere.

“If you change the climate then you can see that you’re creating a disequilibrium,” says Bowman. “The forests are struggling to recover from it.”

And big business, in the form of the insurance industry, could make a difference in helping realign earth’s climate, but most likely not:

Insurance giant Allianz and the World Wildlife Fund aimed their report, “Climate Change and Insurance: An Agenda for Action in the United States,†at insurance honchos.

“Insurance companies manage risk. And we see [global warming] as the biggest emerging risk to the world,†says Matthew Banks, the Fund’s senior program officer.

“We’d like to see the insurance industry take on this challenge in a more meaningful way,†he says.

Four major hurricanes hit U.S. coasts in 2004 and cost insurance companies an unprecedented $23 billion, but that record was short-lived when Hurricane Katrina alone brought $50 billion in insured losses with claims still being filed.

And the insurance companies:

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, for instance, many insurance companies have cancelled policies in high-risk coastal areas.

“And they’re also increasing premiums,†Anderson says, “many times 100, 200, even 300 percent.â€

A quiet sun and loud forest fires — bye-bye tomorrow.