Today 57 years ago:

(Illustration found here).

(Illustration found here).

Quickly-escalating moments in media time:

Just about everyone who was alive then knows where they were when they heard the news.

How they came to hear — decades before the Internet stitched up the world so that news moves at the speed of light — is itself a remarkable story.

Oswald fired at 12:30 p.m. Dallas time.Four minutes later, the United Press International wire reported: “Three shots were fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade in downtown Dallas.”

Five minutes after that, at 12:39 p.m., UPI moved a flash: “Kennedy seriously wounded perhaps seriously perhaps fatally by assassins bullet.” Radio relayed the first bulletins. Within minutes, ABC, CBS and NBC began non-stop TV coverage.

Pollsters later found that 68-percent of American adults heard the news within a half-hour of the shooting, and 92-percent knew within 90 minutes.

About 47-percent of Americans first heard from radio or TV, and 49-percent heard from other people.

When the Aqueduct track announcer finally relayed the news about a half-hour after the first UPI dispatch, “there was no mass reaction because there was nobody in the crowd who hadn’t heard already,” the Herald Tribune reported.

UPI reporter Merriman Smith first on the physical scene:

Just as the presidential limousine arrived at the Parkland emergency room, ABC Radio cut in to its programming with the UPI report, the first broadcast network to get the word out.

The wire car pulled up just after the presidential limo.

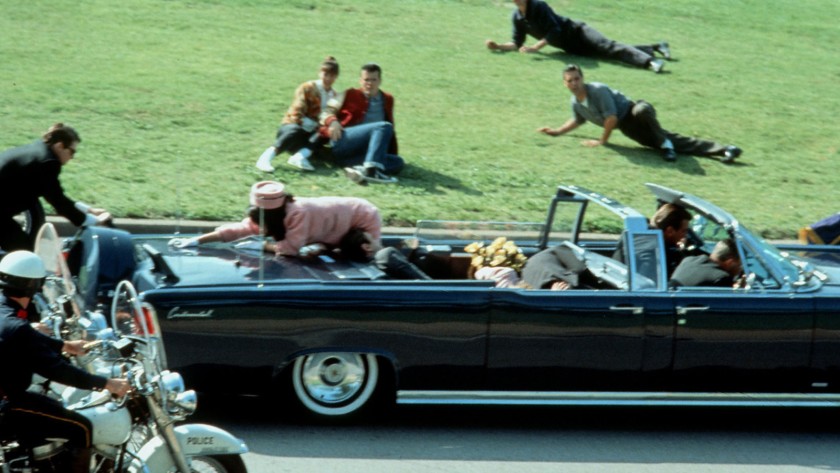

Mr. Smith ran up to the limousine and saw the carnage — Mr. Kennedy was shot in the head.“The president was face down on the back seat. Mrs. Kennedy made a cradle of her arms around the president’s head and bent over him as if she were whispering to him,” he wrote.

Governor Connally was on his back on the floor of the car.

Mr. Smith turned to Clint Hill, Jackie Kennedy’s secret service agent.“How badly was he hit, Clint?” Mr. Smith asked.

“He’s dead, Smitty,” Mr. Hill replied.

Mr. Smith ran inside to an emergency room cashier’s cage and grabbed a phone.

He called in his second bulletin — saying Mr. Kennedy was wounded “perhaps seriously perhaps fatally” — and then a third detailed dispatch quoting Mr. Hill by name as saying: “He’s dead.”

There was no anonymous sourcing of Mr. Smith’s scoop.

And the world stood still.

I was at the time one week away from my 15th birthday and located half-a-world away. My dad was with the DOD’s civil service back then and had recently taken an assignment at an USAF base on Kyushu, Japan’s most-southern of its main islands. We’d only been there for about two months when this happened.

My younger brother work me up in the pre-dawn hours of Saturday to relay the news. I don’t remember how he heard about it. I was pretty naive politically then, and would remain pretty-much so through Nixon — my head was either too far up in the clouds, or up my ass to pay attention. I don’t recall how others at my school took the event the following Monday, or if we even had school.

However, I do vividly remember that as it being Saturday, I headed to the base gym and basketball — was still into sports — but the place was closed. The first indication of the shooting in real time.

I was out of the country for two of the biggest happenings of the late 20th Century — Kennedy’s assassination, and the Beatles coming to New York a couple of months afterwards (which caused me to later-quickly lose interst in sports). As if turned out, the base where we were at was closed a few months later and my family returned to the states.

Nearly 18 months earlier (May 1962), I’d had the chance to see JFK in person when he visited Eglin AFB on the Florida panhandle — I think it was something to do with the USAF Thunderbirds, who performed that day.

Our county school system suspended classes the day of JFK’s visit (I was in the seventh grade), so a friend and I got on Eglin via his aunt, who worked on base, and had staked out a spot along the president’s motorcade route, and seemingly had waited for hundreds of hours under a baking sun when he came into view, standing in back of an open limousine, waving to people on both sides of a narrow, one-lane road adjacent to the flight line.

We waved back, don’t know if he actually saw us, but he did wave with a look in our general direction as his car came pretty close to us.

However, we could see him pretty plain and I remember even 58 years later — big guy, with that way-familiar face on a big head with big shoulders — he quickly disappeared on a turn to the runway and Air Force One.

Long, long ago in a place far, far away…

(Illustration: Front page of the Chicago Tribune, Nov. 23, 1963, found here).

(Illustration: Front page of the Chicago Tribune, Nov. 23, 1963, found here).