Continuing nice autumn weather this late-afternoon Saturday here in California’s Central Valley — we’re having the best outdoorsy-days of the year lately and after last summer’s boiling temperatures, it’s a nice respite.

However, meteorology like a shitload of other things depends near-completely on location.

A horrible for instance — between where I’m located and Florida, where the devastation off Hurricane Ian is horrific and at least 66 people (so far) have died (CNN):

By Saturday evening, Ian was a post-tropical cyclone, continuing to weaken across southern Virginia, and it could drop several more inches of rain over parts of West Virginia and western Maryland into Sunday morning, the National Hurricane Center said.

On Wednesday, Ian smashed into southwest Florida as a Category 4 hurricane, pulverizing coastal homes and trapping residents with floodwaters, especially in the Fort Myers and Naples areas. It pushed inland into Thursday, bringing strong winds and damaging flooding to central and northeastern areas.

The hurricane then made another landfall Friday in South Carolina between Charleston and Myrtle Beach as a Category 1 storm, flooding homes and vehicles along the shoreline and eventually knocking out power for hundreds of thousands more in the Carolinas and Virginia.

Ian is just a sample of our planet’s future — hot water makes for some bad times, and it’s only going to get worse:

This is not normal.

It’s not a fluke.

It’s not an anomaly. @MichaelEMann and @ClimateComms explain how the climate crisis fueled the destructive power of Hurricane Ian. https://t.co/rc9ZaqLyaB— Climate Power (@ClimatePower) October 1, 2022

Details from Michael E. Mann, noted climate scientist and professor of earth and environmental science at the University of Pennsylvania, and Susan Joy Hassol, environmental journalist and director of the non-profit Climate Communication, in the Guardian yesterday:

Ian made landfall as one of the five most powerful hurricanes in recorded history to strike the US, and with its 150 mile per hour winds at landfall, it tied with 2004’s Hurricane Charley as the strongest to ever hit the west coast of Florida. In isolation, that might seem like something we could dismiss as an anomaly or fluke. But it’s not – it’s part of a larger pattern of stronger hurricanes, typhoons and superstorms that have emerged as the oceans continue to set record levels of warmth.

Many of the storms of the past five years – Harvey, Maria, Florence, Michael, Ida and Ian – aren’t natural disasters so much as human-made disasters, whose amplified ferocity is fueled by the continued burning of fossil fuels and the increase in heat-trapping carbon pollution, a planet-warming “greenhouse gas.”

This Atlantic hurricane season, although it started out slow, has heated up, thanks to unusually warm ocean waters. Fiona hit Puerto Rico as a category 1 hurricane (subsequently strengthening to a powerful category 4 storm), and hundreds of thousands of people there are still without power. The storm barreled on into the open Atlantic, eventually making landfall in the maritime provinces to become Canada’s strongest ever storm. Then came Ian, which feasted on a deep layer of very warm water in the Gulf of Mexico.

Human-caused warming is not just heating the surface of the oceans; the warmth is diffusing down into the depths of the ocean, leading to year after year of record ocean heat content. That means that storms are less likely to churn up colder waters from below, inhibiting one of the natural mechanisms that dampen strengthening. It also leads to the sort of rapid intensification we increasingly see with these storms, where they balloon into major hurricanes in a matter of hours.

They try to present a front of optimism, but the words are hollow. Both Mann and Hassol know we’re in really, really bad shape, but don’t want to drive people into despair of hopelessness, which is where we are at the moment.

Peter Kalmus, climate scientist, and author of “Being the Change: Live Well and Spark a Climate Revolution,” explains hurricanes are most-obvious examples of the horrors of the accelerating climate crisis via an op/ed this morning in the Guardian — Kalmus has a warning after relaxing the seriousness of climate change 16 years ago:

But things have turned out worse than I dreamed possible. I underestimated the depth and intransigence of society’s collective climate denial. Despite climate breakdown being far more intense by 2022 than I thought it would be – it all feels like a decade or two ahead of schedule, somehow – the world still isn’t treating global heating like the emergency it is.

To understand what an emergency we are now in, the scale and variety of the climate damage we’ve already incurred, you only need to look at a few of the most recent disasters. Hurricane Ian has just pummeled Cuba and Florida. The full extent of the disaster will only be revealed in the coming days and weeks, although first looks are shocking. But we do know with certainty that Ian was supercharged by global heating through several well-understood fundamental physics pathways.First, hurricanes are heat engines, powered by large expanses of hot ocean. The ocean is absorbing over 90% of the excess energy trapped in the Earth system by human greenhouse gas accumulation, and this means more available energy for more intense storms. Second, a hotter atmosphere can hold more water vapor, which (along with hotter ocean water and stronger winds) translates into more rain. Third, higher sea levels from accelerating land ice melt and ocean thermal expansion mean additional supercharging of storm surges relative to established coastlines and low-lying land. All of these supercharging mechanisms will continue to worsen as global heating itself worsens.

We’re in some hard-pressed times. I, too, was a late-comer to climate change and didn’t see the horror of emissions and fossil fuels until 2007 and the UN IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, which pronounced for the first time: ‘“Warming of the climate system is unequivocal, as is now evident from observations of increases in global average air and ocean temperatures, widespread melting of snow and ice and rising global average sea level. … Most of the global average warming over the past 50 years is “very likely” (greater than 90 percent probability, based on expert judgement due to human activities.”‘

Now more than 15 years later, we be in bad shape.

Despite it all, here we are once again…

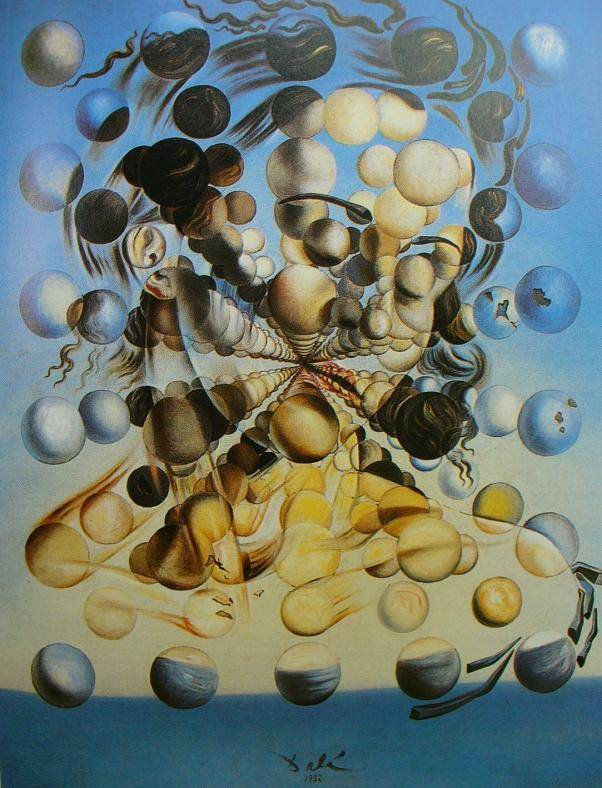

(Illustration out front: Salvador Dalí’s ‘Galatea of the Spheres,’ found here.)

(Illustration out front: Salvador Dalí’s ‘Galatea of the Spheres,’ found here.)