Rain and wind this Saturday morning here in California’s Central Valley — a familiar story for weeks now — and an even-bigger storm is expected later today. Forecasts call for a kind of letting-up respite of all this wet shit maybe the middle of next week.

If nothing else, a welcome sign.

My kids have been in town this past week and I haven’t had the time to post during that time — just attempting to say dry during the visit. It was wonderful, but seemingly short (like all these types of get-togethers) and with the rain it made it feel even more transitory.

And some background to the amount of wet (via AccuWeather):

Approximately 24 trillion gallons of water have fallen across California since the stormy pattern commenced at the end of December with many areas measuring several months’ worth of rain in less than three weeks. This is more than three times the volume of water in Lake Champlain and enough water to fill more than 36 million Olympic-sized swimming pools.

“Large portions of Central California received over half their annual normal precipitation in the past 16 days with the sequence of atmospheric rivers since December 26,” the National Weather Service said on Wednesday. California experienced its third-wettest 24-hour period since 2005 from 4 a.m. PST Monday through 4 a.m. PST Tuesday, only behind Jan. 9, 2017, and Jan. 5, 2008.

San Francisco measured more rain in the first 11 days of January (5.89 inches) than during the first 11 months of 2022 (3.76 inches). People in downtown San Francisco on Tuesday afternoon were also pelted by pea-sized hail as a strong thunderstorm swept through the Bay Area.

Although we did experience some sunshine midweek, not so coming today:

Impressive NCFR (Narrow Cold Frontal Rainband) composed of broken segments of very intense /torrential rainfall, embedded lightning, & locally strong wind gusts to 50+ mph is draped from north to south across Sacramento Valley from Redding south to Davis (moving eastward). #CAWx pic.twitter.com/FsTFTtKtWz

— Daniel Swain (@Weather_West) January 14, 2023

This particular storm is so serious, our local government postponed the annual MLK parade, scheduled for Monday, until Feb. 18 when hopefully life will be drier and more suitable.

Californa Gov. Gavin Newsom is expected to visit here this afternoon, and it will be a wet, windy take — portions of my town has flooded, especially along a creek just east of my location.

Per the local newspaper, the Merced Sun-Star just a short while ago:

Dump trucks and other large equipment are hauling boulders to the creek to stop flooding, noted Jennifer Flachman, public information officer for the city of Merced. Friday, city officials were filming a safety video on the bike path near Bear Creek.

“We turned around for maybe a few seconds and portions of the bike path slid into the creek,” she said. There was no warning and the collapse of the bike path happened relatively quietly, highlighting the how quickly things can turn dangerous, she noted.

“We would like for people to stay out of the Bear Creek area. Stay off the bike paths,” she said. “Please be mindful where you’re walking or driving.”

It’s been that precarious.

And statewide, it’s been a mess — from CNN, also just a short time ago:

Another round of heavy rain already is falling Saturday on the Golden State, where extreme drought fueled by the climate crisis has given way in recent weeks to massive flooding amid a catastrophic sequence of ultra-wet atmospheric rivers – long, narrow regions in the atmosphere that transport moisture thousands of miles. Recent storms have killed at least 18 people and left tens of thousands at a time without power.

Over 25 million people again are under flood watches across much of California’s central coastline, as well as the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys. Though this weekend’s rain tally will be lower than previous storms, the threshold for flooding also is much lower because the ground is fully saturated in many areas.

“This atmospheric river is more progressive than some of the other atmospheric rivers that have occurred in recent weeks, which should help to limit the extent of the flooding potential,” the Weather Prediction Center said. “All that being said, just about all of California; from the coast and both the Shasta and Sierra Nevada on south to the Transverse Range feature soil moisture percentiles greater than 95%.”

All this shit and climate change? California dreaming:

#California infrastructures are definitely not ready for #ClimateCrisis and #climatechange – is it too late already ? #GlobalWarming #Californiastorm pic.twitter.com/sxJKRnzoky

— Guillaume Bourcy (@GuillaumeBourcy) January 14, 2023

One major question with all these storms and accompanying water is how will it affect our drought, which we’ve been drenched in for decades. In the advent of climate change, a lot of knowledgeable people have described our situation as “weather whiplash” — an environment going from dry to wet one season/year to another.

A look at this phenomenon from Vox last Wednesday:

The term “weather whiplash” has been around for at least a decade, and it means what it sounds like: a quick shift between two extreme and opposing weather conditions. From drought or fire to floods, from severe cold and snow to heat waves.

California’s current crisis is a perfect example. The state is experiencing its worst drought in roughly 1,200 years. Millions of residents have been asked to cut their water usage. But the ongoing storms turned the extremes around: Much of the state has received rainfall amounts that are 400 percent to 600 percent above average, resulting in some of the worst floods in California history. (So far, the water hasn’t been enough to quench the drought, and there isn’t sufficient infrastructure to capture the flood water for later use.)

Last summer, Dallas experienced a similar whiplash effect. For days on end, temperatures soared above 100 degrees. More than two months passed with no rainfall. Then a rainstorm struck, dumping more than a foot of water in parts of the city in half a day. A similar story played out in the Southwest, where exceptionally warm weather fueled wildfires, which were followed by exceptional quantities of rain.

[…]

Yes, some scientists say: Climate change could be making whiplash events more frequent in the decades to come, though there are some key uncertainties.

A study published in 2022, for example, found that while whiplash weather events haven’t become more common in recent decades, they’re likely to increase in the future due to warming. Another paper, from 2020, found that in certain regions, “seesaws” between drought and intense rainfall have become more common (the study doesn’t say whether climate change is the culprit).

“These sudden shifts are highly disruptive to all sorts of human activities and wildlife, and our study indicates they’ll occur more frequently as we continue to burn fossil fuels and clear-cut forests,” said Jennifer Francis, the lead author of the 2022 study and senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center.

And why all these storms we’re going through right now may not be enough to make us drought-free. Climate change the culprit.

An interesting, and foreboding take on this comes from an interview with Christine Shields, climate scientist at The National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), at Salon this morning — the ‘new normal‘ conclusion:

One of the things that I do in terms of climate change research is to try to understand what’s going to happen to these types of things in the future. And so if we just separate this out into water and wind again, we know very clearly what’s going to happen with atmospheric rivers in terms of the water content. As the global temperature increases, the amount of water that we can evaporate into the atmosphere will also increase. So just by the fact that we have warmer surface temperatures in the troposphere— which is the lower part of the atmosphere — is just guaranteeing that we’ll have more water available to atmospheric rivers. So the atmospheric rivers will tend to be definitely wetter, with potentially more intensive rain periods.

“But one of the things that is really ongoing research is whether or not the numbers of atmospheric rivers — if there will be more or if there will be less. We’re seeing there’s research out there, not mine, that suggests that you’re going to have more of these, you’re gonna have more drought and then more intense rain periods. And so we might be oscillating from more severe drought to super wet, super dry, super wet, super dry — these swings that can be potentially destructive.

That’s why time’s a-wasting:

Soaking wet in the dry, yet here we are once again…

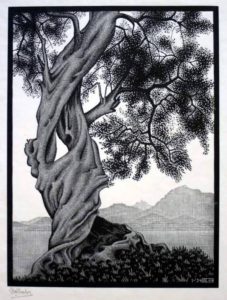

(Illustration out front: MC Escher’s ‘Old Olive Tree, Corsica‘ (1934). and found here)

(Illustration out front: MC Escher’s ‘Old Olive Tree, Corsica‘ (1934). and found here)