A tight, chilly wind near sunset in California’s Central Valley this Sunday, drawing close to the end of another gorgeous day in a week-long respite from those ghastly atmospheric rivers.

It’s been a time of drying out for our state and of counting the loss and the dry of a ‘whiplash weather’ pattern set to explode again in the near future. However, rain is not in the forecast until at least next month — time enough for right now, I suppose.

Time, too, for a review of our shifting, dangerous climate:

State of the climate: How the world warmed in 2022 | @hausfath

Read here: https://t.co/VvUxY1Ja6h pic.twitter.com/2WAmfdcREI

— Carbon Brief (@CarbonBrief) January 22, 2023

Nutshell details at Carbon Brief from last week:

- Ocean heat content: It was the warmest year on record for ocean heat content, which increased notably between 2021 and 2022.

- Surface temperature: It was between the fifth and sixth warmest year on record for surface temperature for the world as a whole, at between 1.1C and 1.3C above pre-industrial levels across different temperature datasets. The last eight years have been the eight warmest years since records began in the mid-1800s.

- A persistent triple-dip La Niña: The year ended up cooler than it would otherwise be due to persistent La Niña conditions in the tropical Pacific. Carbon Brief finds that 2022 would have been the second warmest year on record after 2020 in the absence of short-term variability from El Niño and La Niña events.

- Warming over land: It was the warmest year on record in 28 countries – including China, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain and the Uk – and in areas where 850 million people live.

- Extreme weather: 2022 saw extreme heatwaves over Europe, China, India, Pakistan and South America, as well as catastrophic flooding in Pakistan, Brazil, West Africa and South Africa. Climate change played a clear role in increasing the severity of all of these events.

- Comparison with climate model data: Observations for 2022 are close to the central estimate of climate models featured in the IPCC fifth assessment report.Warming of the atmosphere: It was the seventh or eighth warmest year in the lower troposphere – the lowest part of the atmosphere – depending on which dataset is used. The stratosphere – in the upper atmosphere – is cooling, due in part to heat trapped in the lower atmosphere by greenhouse gases.

- Sea level rise: Sea levels reached new record-highs, with notable acceleration over the past three decades.

- Greenhouse gases: Concentrations reached record levels for CO2, methane and nitrous oxide.

- Sea ice extent: Arctic sea ice saw its 10th lowest minimum extent on record, and was generally at the low end of the historical range for the year. Antarctic sea ice saw a new record low extent for much of 2022.

- Looking ahead to 2022: Carbon Brief predicts that global average surface temperatures in 2023 are most likely to be slightly warmer than 2022, but are unlikely to set a new all-time record given lingering La Niña conditions in the first half of the year.

And the warming is continuing, maybe accelerating:

The focus on global surface temperature as a key metric of climate change is important, but it can obscure very different rates of change across the planet.

For example, while most of the Earth’s surface is covered by oceans, nearly all human settlements and activities are in land areas. The land has been warming around 70% faster than the oceans – and 40% faster than the global average – in the years since 1970.

[…]

While the world as a whole has warmed by around 1.3C since the pre-industrial period (1850-1900) in the Berkeley Earth dataset, land areas have warmed a much larger amount – by 1.8C on average. In contrast, the oceans have warmed more slowly – by around 0.8C since pre-industrial times. (See Carbon Brief’s guest post on why the land and ocean warm at different rates.)

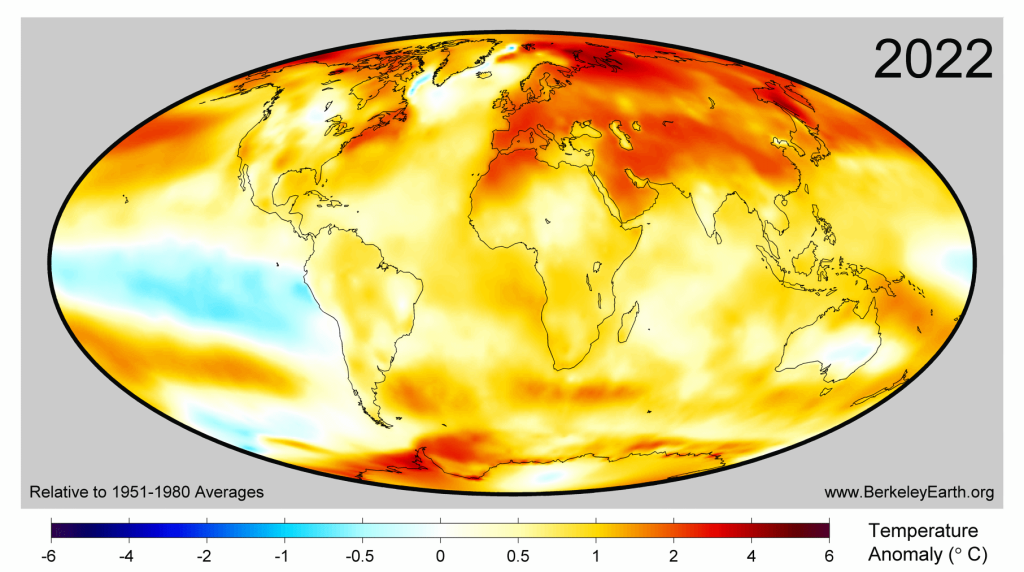

Different parts of the land and ocean are also warming at different rates. The warmth in 2022 covered large regions of the world, with particularly anomalously high temperatures over Europe, China, the Middle East and parts of the Arctic, and relatively cool temperatures over the tropical Pacific due to La Niña conditions. The figure below, from Berkeley Earth, shows the average annual temperatures, relative to 1951-80, across the world for the year.

In addition to being the fifth or sixth warmest year on record for the surface and setting a new record for ocean heat content, 2022 saw many climate extremes around the world. These include record-breaking extreme heat events in the UK and Europe, China, India and Pakistan and South America, and catastrophic flooding in Pakistan, Brazil, West Africa and South Africa.

In all of these cases, scientists working with the World Weather Attribution team have found that these extremes were made worse by human-driven climate change. At the same time, researchers found more limited evidence of the role of climate change in worsening droughts in both Madagascar and the Sahel region of Africa.

In 2022, 28 countries saw their warmest year on record according to Berkeley Earth. This includes Afghanistan, Andorra, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, China, Croatia, Fiji, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Kyrgyzstan, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, Morocco, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Portugal, San Marino, Spain, Switzerland, the UK, Tajikistan, Tonga, Tunisia and Vanuatu.

And for this coming year:

Here, Carbon Brief provides its own prediction of likely 2023 temperatures using the NASA GISTEMP dataset – and based on a model using the year, temperatures over past three months, and projections of El Niño/La Niña conditions over the next six months.

[…[

While the uncertainties are still wide at this point, we find that 2023 is very likely to be between the third and ninth warmest year on record, with a best estimate of being the fifth warmest on record – similar to 2022. If an El Niño event develops in late 2023, however, it will make it likely that 2024 will set a new record.

And to conclude:

While the Met Office, Berkeley Earth and Carbon Brief estimates all have 2023 as similar (albeit a tad warmer) to 2022, with a relatively small chance of setting a new record, Dr Schmidt predicts that 2023 has a real chance of tying with 2016 and 2020 as the warmest year on record. It is worth noting that the Berkeley Earth projection ended up being the most accurate last year in predicting 2022 temperatures.

However, what matters for the climate is not the leaderboard of individual years. Rather, it is the long-term upward trend in global temperatures driven by human emissions of greenhouse gases. Until the world reduces emissions down to net-zero, the planet will continue to warm.

It is almost certain that the next time the world sees a moderate to strong El Niño event, that year will set a new all-time temperature record.

And to finish out some easy-to-choke-on shit, Al Gore at Davos last week:

Some nudging, and hopefully not more “blah, blah, blah.”

Heated or unheated action, yet once again here we are…

(Illustration out front found here.)

(Illustration out front found here.)