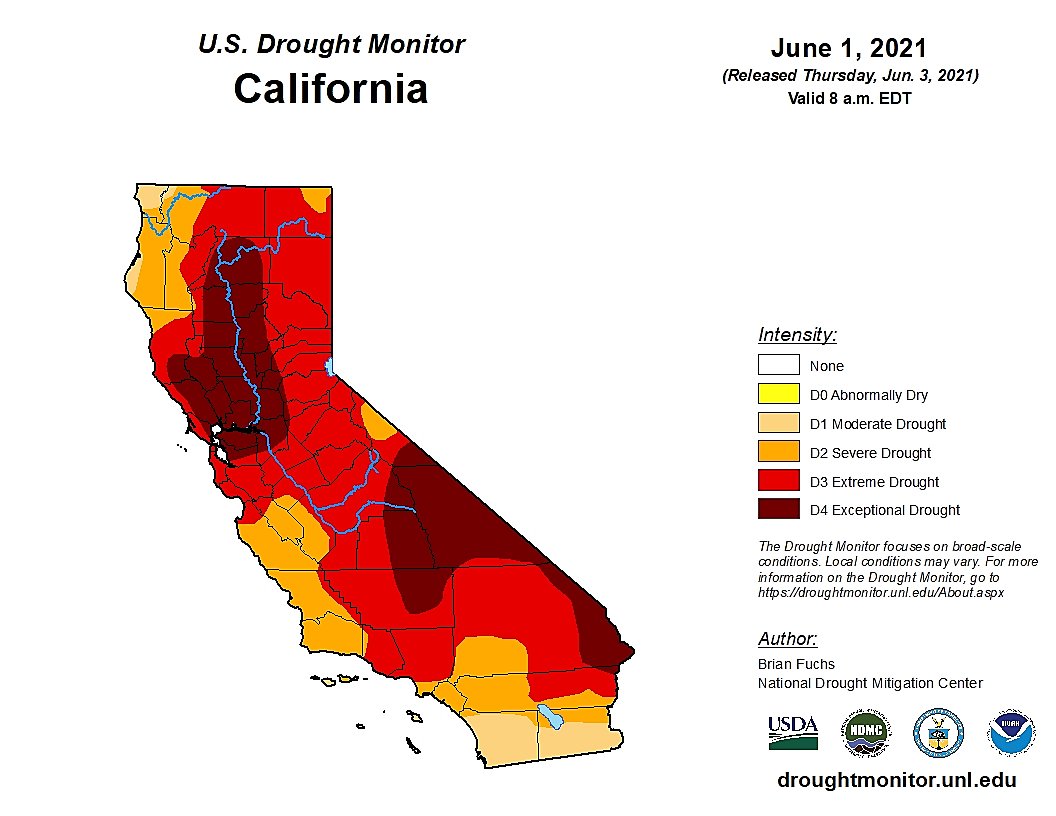

(Illustration: US Drought Monitor, California, found here).

(Illustration: US Drought Monitor, California, found here).

Sunny but cooler than normal this Monday afternoon in California’s Central Valley, a seemingly off-day from the heat we’ve experienced the last week or so — yet the weather still carries the imprint of a scorched-earth era again, which appears part of our statehood status for the nowadays.

In a direct offshoot from a way-dry winter, California — and just about the entire Western US, especially the Southwest — has plunged into a drought genre of life — lack of water is starting to impact farming, livestock, energy supplies, and eventually everything. Already the dry has created forest fires, and that aspect will only get worse as we go along into the blast-furnace of the summer.

Here in California, this might be the shittiest drought ever — a look-see via the Guardian this afternoon:

Governor Gavin Newsom has declared a drought emergency in 41 of the state’s 58 counties.

Meanwhile, temperatures are surging as the region braces for what is expected to be another record-breaking fire season, and scientists are sounding the alarm about the state’s readiness.“What we are seeing right now is very severe, dry conditions and in some cases and some parts of the west, the lowest in-flows to reservoirs on record,” says Roger Pulwarty, a senior scientist in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa) physical sciences laboratory, adding that, while the system is designed to withstand dry periods, “a lot of the slack in our system has already been used up”.

…

Drought is not unnatural for California. Its climate is predisposed to wet years interspersed among dry ones.

But the climate crisis and rising temperatures are compounding these natural variations, turning cyclical changes into crises.Drought, as defined by the National Weather Service, isn’t a sudden onset of characteristics but rather a creeping trend. It’s classified after a period of time, when the prolonged lack of water in a system causes problems in a particular area, such as crop damages or supply issues.

In California, dry conditions started to develop in May of last year, according to federal monitoring systems.The effects really began to show in early spring 2021, when the annual winter rainy season failed to replenish the parched landscape and a hot summer baked even more moisture out of the environment.

By March, conditions were dire enough for the US agriculture secretary, Tom Vilsack, to designate most of California as a primary disaster area.

Just two months later, 93-percent of the south-west and California was in drought, with 38-percent of the region classified at the highest level.“When you have droughts with warm temperatures, you dry out the system much faster than you’d expect,” says Pulwarty, adding that climate change can make droughts both more severe and harder to recover from.

“It is not just how much precipitation you get — it is also about whether or not it stays as water on the ground.”

Well, that's it. California's winter snowpack is basically gone. Two months early.#drought#climatechange pic.twitter.com/GOru2PH8tP

— Peter Gleick ?? (@PeterGleick) May 27, 2021

Meanwhile, California has been getting warmer, and 2020 brought some of the highest temperatures ever recorded.

In August of last year, Death Valley reached 130F (54C) and a month later, an area in Los Angeles county recorded a 121F (49.4C) day — the hottest in its history.Heat changes the water cycle and creates a thirstier atmosphere that accelerates evaporation. That means there’s less water available for communities, businesses, and ecosystems.

It also means there will be less snow, which California relies on for roughly 30% of its water supply.“The snowpack, in the context of the western US and specifically in California, is really critical for our water supply,” says Safeeq Khan, a professor at University of California, Merced, who researches the climate crisis and water sustainability.

“The snowpack sits on the mountain and melts in the spring and early summer. That provides the buffer to overcome the extreme summer heat,” he explains.

…

“If we are worried about this year we are really playing the short game,” says Doug Parker, the director of the California Institute for Water Resources. “It’s next year that I think is more important.”The water system, he says, is designed to handle short-term shortages.

“When you get into three, four, five years in a row of drought — that’s when things really start to get serious. We all wish we knew what was going to happen next winter.”

The future is not all that wonderful. And just to make matters even worse — fucking climate change, and our worse year ever! Despite the industrial slowdown with the COVID-19 pandemic, emissions surged and seem to be accelerating — per The Washington Post, also this afternoon:

But the idle airplanes, boarded-up stores and quiet highways barely made a dent in the steady accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which scientists from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said Monday had reached the highest levels since accurate measurements began 63 years ago.

The new figures serve as a sober reminder that even as President Biden and other world leaders make unprecedented promises about curtailing greenhouse gas emissions, turning the tide of climate change will take even more massive efforts over a much longer period of time.

…

“Fossil fuel burning is really at the heart of this. If we don’t tackle fossil fuel burning, the problem is not going to go away,” Ralph Keeling, a geochemist at Scripps , said in an interview, adding that the world ultimately will have to make emissions cuts that are “much larger and sustained” than anything that happened during the pandemic.Scientists from Scripps and the NOAA said on Monday that levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide peaked in May, reaching a monthly average of nearly 419 parts per million.

That represents an increase from the May 2020 mean of 417 parts per million, and it marks the highest level since measurements began 63 years ago at the NOAA observatory in Mauna Loa, Hawaii.

Twice in 2021, daily levels recorded at the observatory have exceeded 420 parts per million, researchers said.“While 2020 saw a historic drop in emissions, the fact that at certain points more than half the world’s population was under lockdown, and emissions ONLY fell 6-percent, should be a sobering reminder of how staggeringly hard it will be to get to net zero and how much more work we have to do,” Jason Bordoff, founding director of Columbia University’s global energy center, said in an email.

Pieter Tans, a senior scientist with NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory: ‘“The goals so far are themselves insufficient, even after having been beefed up … We’re running out of time. The longer we wait, the harder it gets.”‘

In rupturing pulse in the meantime, we dry-drought — Huh?

(Illustration out front: Salvador Dali’s ‘Soft Watch at the Moment of First Explosion,’ found here).

(Illustration out front: Salvador Dali’s ‘Soft Watch at the Moment of First Explosion,’ found here).