Humid-hot this late-afternoon Saturday here in California’s Central Valley — the first day in a few weeks we didn’t see triple-digit temperatures. California has been cooking and we’re now forecast for mild weather for a while.

Odd environment in southern California tonight, going from a dry-bake to flooding is a matter of hours.

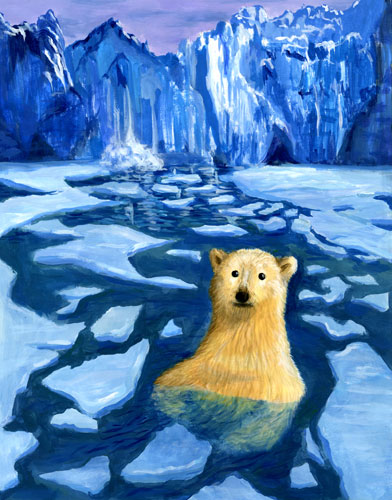

Amid news from all over, from the death of Elizabeth (and all its numerous side-stories) to the finally-encouraging war news out of Ukraine, I saw this tweet about a problem so enormous, it overshadows all life — climate change:

This is what I’m worrying about today https://t.co/T1bM2NUzNV pic.twitter.com/tkyr9gzzVz

— Molly Jong-Fast (@MollyJongFast) September 10, 2022

In reporting climate-change news, I’d discovered quite some time ago the shit is getting bad, and getting bad quicker.

And sad to say, the bottom line is it’s another ‘worse-than-originally-figured‘ climate research.

Science journalist Elizabeth Rush at The New York Times last week nailed it in the saga of the Thwaites Glacier in West Antarctica — the “doomsday glacier“ is an indication of where the world is headed:

This week Nature Geoscience published a paper analyzing the data from that submarine. The authors, many of whom were on board the vessel with me, suggest that sometime over the past couple hundred years, Thwaites retreated at two to three times the rate we see today. Put another way: At the cold nadir of the planet, one of the world’s largest glaciers is stepping farther outside the script we imagined for it, likely defying even our most detailed projections of what is to come.

…

I am not yet 40, and in my lifetime, climate change has gone from something that we thought would happen in the future to something happening now to something accelerating at such a surprising pace that it makes most of our feeble attempts to reckon with it outdated before they even get underway. This great acceleration has now reached all the way to Antarctica.

Things we used to classify as inert — ice shelves, glaciers, ice caps — are springing into action, demanding we recognize that here and there are not so distant after all. It took us nearly a month to arrive at the edge of Thwaites. By many measures, it is one of the most remote regions on earth. But despite the distance, what happens there is shaping us just as much as we are shaping it. If we can begin to recognize the agency of this faraway glacier, we will be one step closer to embracing the profound humility that climate change demands.

Global calamity aside, once again here we are…

(Illustration out front found here.)

(Illustration out front found here.)