NOTE: This a re-post of a significant memory detail from the distant past, seemingly really, really relevant today. This is an essay-like piece of mine from a way-while back, originally published Dec. 30, 2007, at a long-gone site where I tried to put an online news-type magazine together, but quickly failed. Appeared here at Compatible Creatures three years later.

Post theme is ‘watershed,’ a word with two definitions: One a land area that channels rainfall and snowmelt; the other, a historical, dividing marker for a crucially important event or period of time, or a ‘turning point‘ for somebody/something. I’d written that first one on the eve of 2008 (turned out to be hghly-explosiove), and flashbacked to 1968, a way-big-fucking deal of a year for not only America (Vietnam, assassinations, riots, etc.) but in a big way, for me personally, too.

And here now we’re a couple of weeks into another way-most-likely ‘watershed year’ — the most important maybe in all of history, truly at least for America despite the last couple being also high on the shitlist for dangerous, divisive episodes, and beyond the US, will be the biggest global election year ever — and the fate of our future is at stake, from our current system of governance, to how we handle our chaotic, overheating environment.

In the shape of an immediate future, the next 50 weeks or so are going to be one gut-clutching, asshole run.

Near forty years ago was 1968. A very big, long year. Life-altering situations erupted in January and continued until December 1972.

In 1968, a couple of bad shootings — one at a motel, the other in a restaurant kitchen — and a disastrous turning point in a disastrous war high-lighted a tsunami of events, all in just 12 months, although influence would vibrate harshly for at least another four years. And maybe until this present day.

The world, America and this writer were altered forever by happenings in 1968. And as 2008 quickly approaches, a growing sense of strange days-a-coming: 1968 a not-so-distant mirror (a bow to the late historian Barbara Tuchman) to the worsening chaos that might await us.

This 40th anniversary has also gathered a bit of media attention, including a view from retired TV anchor, generational-booster/’greatest generation’ of just damn-great Americans/journalist Tom Brokaw, whose book Boom! Voices of the Sixties: Personal reflections on the ’60s and Today has as theme, the 1960s as a whole and 1968 in particular. Recently, Brokaw’s documentary/book spin-off, 1968 with Tom Brokaw, ran on cable’s History Channel.

Brokaw is pure establishment, though, and seems to have of lately appeared as such a heavyset voice of self-appointed experience and knowledge that he comes off more as a blind man (an increasingly irritating one, unfortunately), unable to see or grasp what’s really going on because he’s too-so-grounded into the fabled America Dream: A middle-class vision of America’s greatness with deep roots in 1950s ideals and ideas. The 1960s exposed the now-ridiculous facade of this vision, and 1968 opened up its guts.

And Brokaw, along with many, many others of his generational ilk didn’t then and don’t now, appreciate this exposure.

Another take on 1968 — at least as an excellent ‘what if’ — is a well-written piece, though fairly long, by Joe Strupp, a senior editor at Editor&Publisher, which examines the emerging power of blogs on political-news reporting. Quick news information could have had a major impact on 1968’s politics, Strupp says, and maybe even could have kept Richard Nixon out of the White House. (The story was posted on E&P’s Website 12/17/07).

Forty years ago right now, December 1967, the US was balanced like Humpty Dumpy, perched high on the continuation of the dream: Good people in government doing good things to help America remain free. And as an aside to modern technology: No looking under the covers at what America’s leaders were actually doing as opposed to what they were saying — Watergate (which was still in the future) would alter how America viewed its government. The Pentagon Papers scandal, My Lai and Easy Rider were still a couple of years away.

Jack Kennedy’s assassination (coupled with the Beatles arrival in America a month or so later) was a watershed period for the offspring of Brokaw’s ‘greatest generation:’ the baby boomers, named so because of the spike in births from just after World War II (1946) until the early 1960s, peaking in 1957. These boomers, at least in the vast, wad-like middle America, accepted the life expectancy of their parents, the values, the outlook and the reliance on hard work to achieve success.

And this attitude of success was geared to education and the world view of America as saint.

In 2007, 23 percent of America’s population was these boomers, about 78 million, including Bill and Hillary Clinton, George Bush and this writer.

Also in 1967, life was viewed in large context via black and white. Three years earlier, only 3.1 percent of TV households had a color television set. And just in the 1966-’67 TV season did all three networks go with full-time, all-color programming. The country was beyond Ozzie and Harriet, but Donna Reed still waited at the foot of the stairs, ready to sort out all of life’s little black-and-white problems. Color television sets climbed to 50 percent of TV households by 1972 and continued upward.

America also saw the world as black and white, especially in foreign policy, and especially in dealing with the Russians (the USSR, but the short version for Americans was “Russians”). America as white, the Russians as black. And whatever America did to fight the Russians was A-Okay.

And in 1968, the American dream suffered a fatal tear in the fabled fabric.

In December 1967, there were 474,000 US troops in South Vietnam. The US had been there since 1963 with commitment escalating every year. In a US government-created “success” campaign in the fall of ’67 to spin away the unsuccessful, tiring conflict, the military’s mood was way upbeat, with many commanders in the field reporting the North Vietnamese army was in its last throes, or words to that effect. Overall US Vietnam commander, Gen. William Westmoreland, in a speech at the National Press Club in November 1967, said North Vietnam was “unable to mount a major offense…”

The American public, however, had become somewhat skeptical of the war. Concern was there: In public opinion polls 25 percent of Americans in 1965 thought the war was a mistake, that number had climbed to 45 percent by December 1967.

The ugly truth of the entire misguided adventure in Vietnam would shortly erupt.

Despite Westmoreland’s big mouth, less than a month into the new year, on Jan. 31, 1968, at the beginning of the lunar new year of Tet, 70,000 North Vietnamese regular troops attacked all across South Vietnam in lighting strikes that caught the American forces completely off guard. One group of commandos even took the US embassy in Saigon. Although North Vietnam’s military campaign was eventually defeated, the war was lost for America, though the conflict would continue for another five years.

A problem: All those color TV sets receiving the horror into America’s living rooms.

Vietnam had become a visual war and the Tet offensive proved a picture is indeed worth a thousand words. After touring and reporting from the war zone, CBS anchor Walter Cronkite opinionated the entire operation in Vietnam was lost and that commentary vibrated throughout America, even to the White House. President Lyndon Johnson, whose popularity has started to descend even before Tet, saw the bottom fall out: “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost America.”

Demonstrations on college campus and urban centers became almost a common every-day experience.

Then Johnson, contrary to ‘normal’ re-election bids for sitting presidents, was nearly beaten in the New Hampshire primary by upstart Sen. Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, whose “Clean for Gene” campaign (young voters cutting beards and hair) galvanized a new anti-war voting block. Four days after New Hampshire, Sen. Robert Kennedy of New York entered the presidential race.

And less than a week after the start of the Tet offensive, on Feb. 5, 1968, a naive, a 19-year-old meatball of a boy eloped with a redhead to Bixoli, Miss. A little-known disaster in a year of major disasters, but a personal defect which would last years. In fact, as a direct and indirect result of that particular day, my intellectual-judgment growth was stumped, retarded so badly (the marriage, which lasted five years, wasn’t entirely to blame) I stood in a slight drizzle in November 1972 to cast a vote for Richard Nixon. An example of the retardation: A photo op/campaign ad of Nixon taking an apparent contemplative afternoon stroll on the beach clad in tie and Wingtips — and me “not” screaming, What an asshole!

A controlled TV image right out of The Selling of the President 1968, by Joe McGinnis (the definitive analysis on how Nixon staged his winning 1968 presidential bid) used four years later to create an impact on a dis-informed, dumb shit 22-year-old.

Shame of the ’72 Nixon vote will be carried to my grave. In slight defense: It didn’t take me long to thaw to the truth of the matter. Within a couple of weeks of that pathetic ballot box, was Nixon’s Christmas bombing of North Vietnam, which ushered in my age of enlightenment and saw the close of America’s rebellion with its existence. Although Watergate had already happened — Bernstein and Woodward were already cranking out Washington Post stories — the public-at-large’s energy against the establishment had run out of air. In late spring 1972, the University of Florida (where I would attend journalism college in the fall after being discharged from the US Air Force) was the scene of the last, big demonstration/riot by young people, raging against the machine that was America.

As periods go, the long 1968 was way-indeed a watershed year, both on a personal, backyard level and with America as a whole. War, assassinations, riots and Alice’s Restaurant created an explosion that rocked at least two generations.

The shock was even greater because of the year before: The summer of 1967 was the last period of innocence for a very-large swath of baby boomers, from the naivete of the ‘flowers in your hair’ aura to an almost apolitical dream-like vision of a bright, unclouded future.

And as the new year of 2008 quickly approaches, the situation 40 years ago adds a curdle to the already sour outlook. Another disastrous war — in many ways, even worse than the one in 1968 — is approaching its fifth year with no discernible end in sight. A vast amount of Americans want it to end, get the US troops home. Americans want things back to normal, maybe like they were prior to Sept. 11, 2001, but that is long, long gone. This is the period of the infamous “now normal,” where guidelines and perceptions shift with the fright.

What a difference in 40 years. Now, there’s nowhere to run, nowhere to hide, nowhere to start over, plan for tomorrow. In Biblical lineage, 40 years is considered a generation; the big question: Can this generation survive.

There’s no more America perched like Humpty Dumpty.

Now America is in an after-the-fact mode: People scurrying around to put Humpty back together again.

History to kick us in the ass, or not, yet here we are once again…

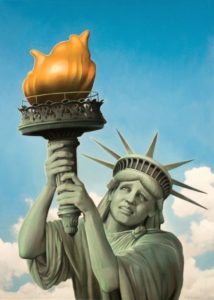

(Image out front by illustrator and portrait painter, Tim O’Brien, and can be found here.)

(Image out front by illustrator and portrait painter, Tim O’Brien, and can be found here.)