Fog-city this early Friday on California’s north coast, and quiet — no sound from westward and the Pacific Ocean, either.

Fog-city this early Friday on California’s north coast, and quiet — no sound from westward and the Pacific Ocean, either.

Clear, crisp and sunny fall-like morning’s we’d had the past three/four days are gone, back to a our summer-extension’s normal of a sad-sack’s deep gray.

And a drought-related bit: Appears less and less likely there’s going to be any kind of a strong El Niño event this year to uplift water worries here in California — yesterday, NOAA slightly lowered the odds of an event from a strong 65 percent in early August, down a month later to a 60-65 percent chance, though, the drop appears tiny, it’s on a downward slope. Earlier in the year — 80 percent.

Unfortunately, too, if an El Niño does appear, supposedly it’ll be really weak-ass.

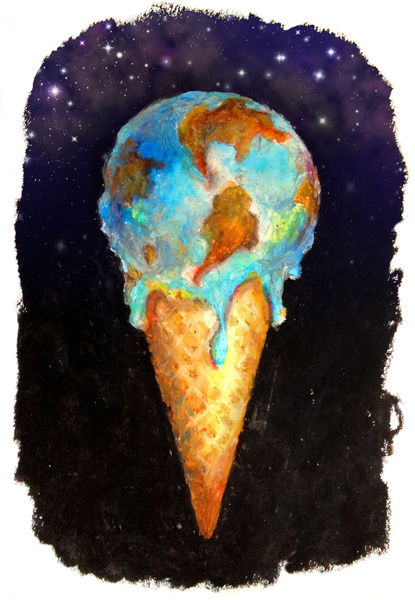

(Illustration found here).

Nearly 40 million of us Californians live in some form of bad drought — more than 55 percent of the whole state is under an “exceptional drought” ranking (the worst), while the entire state is considered just below the worse, and in “severe drought” — other than that: “…more severe in many ways than a landmark drought in the late 1970s, and is comparable, if not worse than, events that occurred since instrument records began in the mid-19th century.”

Even Conan O’Brien is pitching — in a PSA for a water alternative.

From Mashable and that wimpy El Niño:

El Niño events are characterized by warmer than average sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific, and they add heat to the atmosphere, thereby warming global average temperatures.

Already, in June, global ocean temperatures were the warmest they had ever been since recordkeeping began in 1880, thanks in large part to above average sea surface temperatures in the Pacific.

El Niño events typically occur once every three to seven years and can also alter weather patterns around the world, causing droughts and floods from the West Coast of the U.S. to Australia and eastern Africa.

…

“It was pretty apparent when we were seeing fairly warm sea surface temperatures across the tropical pacific, and across the board there was a fairly lackluster atmospheric response,” according to Michelle L’Heureux, a scientist with the Climate Prediction Center in Maryland.

Now, though, the trade winds and other indicators are “a little more of a mixed bag,” she said, which may indicate the emergence of an El Niño in the next few months.

L’Heureux told Mashable that most of the computer models that forecasters use to help predict El Niño events had been predicting an earlier onset of an event, which has not been the case.

Now, those models are showing a later onset, and most still favor the occurrence of an El Niño.

“We’re not completely clear on what season it is going to emerge in,” she said.

“The onset time is being progressively pushed back.”

Interestingly, she said that in the past 10 years, many El Niño and La Niña events have kicked off later in the year, in either late fall or early winter, compared to previous decades.

However, it is not yet clear why that is, and whether it is linked to natural climate variability, manmade climate change, or both.

The intensity of an El Niño, if indeed one occurs at all, will help determine what the impacts will be.

According to L’Heureux, for weak El Niños, the impacts are harder to predict and more subtle than they are with strong El Niños.

L’Heureux said that based on observations and computer model forecasts, it’s “very unlikely” that a 2014-2015 El Niño would be a strong event.

“Our consensus forecast is that folks should at least expect a weak event,” she said.

The warming environment will screw with everything. Although there’s been studies linking climate change with stronger, more intense El Niño events, this year’s version seems to be acting different, and might be different, yet…: One thing is certain, says Michael McPhaden, an oceanographer with NOAA in Seattle, Washington: however this year’s El Niño watch plays out, it will influence research for several years.

“Why has nature surprised us in this startling way?” he asks. “Figuring it out is going to be really important.”

And figuring how to slow the overall warming is pretty important, too. The rest is just a Niña.

(Illustration Out Front: NASA satellite image of California’s drought, late January-early February 2014, found here).