(Illustration found here).

Even as the life in 2018 continues to resemble a terrifying jigsaw puzzle, we still have our illusions of escape beyond a reality gone berserk. This particular post has been collecting dust in my Draft bin more than five years — I’ve played with it, moved words/pictures around, but otherwise left the thing unfinished, undone in a waiting-in-the-wings scenario — until now..

Movies have always been my choice of escape, a flight away from the essentials of normal life, yet at the same time, remain real in a sense. In our peculiar, present situation, the T-Rump represents the worse form of villain, someone way-way wicked, who doesn’t give-a-shit about anyone-or-anything but himself — he’d easily make the list of movie bad guys, and beyond.

His profile of filmography at Wikipedia is long, and in nearly-all the characters, reality TV or not, he’s played himself as asshole villain, usually petty and ignorant.

An example: In “Two Weeks Notice,” a Sandra Bullock/Hugh Grant romantic comedy from 2002, which for awhile earlier this year was on my Netflix rom-com list as antidote to the horror of the T-Rump. Others included “Maid in Manhattan,” “While You Were Sleeping,” and “13 Going on 30,” and so forth…

Grant’s character in ‘Two Weeks‘ is a real estate magnate himself, George Wade, who knows the T-Rump and encounters him at a party, where the T-Rump plays it straight — an intimidating, oafish douche:

T-Rump: Wade.

George Wade: Trump.

T-Rump: I hear Kelson finally dumped you.

Wade: Not exactly, no. We just came to a mutual understanding that she couldn’t bear me for another second, that’s all.

T-Rump: So who’s the new chief counsel? If she’s any good, I’m gonna steal her away.

Wade: I doubt it. She seems quite loyal to me.

T-Rump: Let me be the judge of that.

Wade: All right. I’m not intimidated. I’ll even lead you to her, she’s over there somewhere.

The scene nearly ruined the movie, but not quite.

Movies can be escape, or maybe just a reinstatement of life’s little happenings.

Escaping is one human trait all of us carry.

Our basic instincts originate from just two qualities: Fight or flight; duke-it-out, or run-like-a-scalded dog.

In the physical world, we make judgments all day long, from the minor to the outrageous, and for the vast majority of the time, these moments go unnoticed — in line at Safeway, driving home from work, wherever — as just petty, but near-instantaneous decisions of making escape or not.

From, “Dude, what’s your problem?” to an escapist, “Excuse me,” all in a flash — circumstance, attitudes, and whether confronting an asshole or not, a large part of the encounter.

And in our human brains, the same situation, except worse — the shit there is free-flowing, has no real decision point, and in worse-case scenarios, can put you in an asylum /institute. Or prison.

The human mind a way-most mysterious organ, a mush of gray matter pulsing with the personal narrative of ourselves. And a goodly-portion of that shit up there no one else knows about, and maybe wouldn’t have a clue.

In recalling way-distant, early memories, I can’t piece together any snapshot-experiences which would explain the later formation of myself as gifted escape artist, able to flow from reality to fantasy, and back again. And, of course, all the while creating a ‘normal‘ persona to unsuspecting onlookers, family, friends, whoever. Oh, they know you’re crazy, but shit-on-a-stick, if they only knew how crazy.

This ability, I suppose, is a major feature for about everybody — some more agile than others.

Via Wikipedia: Escapism is mental diversion by means of entertainment or recreation, as an “escape” from the perceived unpleasant or banal aspects of daily life.

It can also be used as a term to define the actions people take to help relieve persisting feelings of depression or general sadness.

As humans moved farther and farther from real, physical toil — the old ‘hunter-gatherers’ routine — there was more time to do stuff, like read. And the closer to the nowadays, the way-more time to read.

Escape into books.

Due to conditions of myself, I didn’t really start reading as a part of life until the sixth grade, maybe due to the enthusiasm of our special reading instructor who came to class three times a week, and really, really like to read, but in reality, books were then enthusiastically-connected to an already-existing escapist condition — movies.

And the very-first of many to come was “The Time Machine,” by H.G.Wells, which launched a great youthful interest in science fiction (as I got older, this morphed into Philip K. Dick).

In the ‘Time Machine‘ movie, Yvette Mimieux shocked a 12-year-old into wanting to build a frickin’ time machine as fast as possible — time wise. Mimieux played Weena of the Eloi and the love interest of the time traveler (Rod Taylor, later of “The Birds” fame).

Anyway, literature paled next to movies, and only added fuel to the film-fire.

Although I’ve no real memory of it, my mother told me later: In the early 1950s, my dad had to work Saturdays, and on his way to work, would drop my off at the local movie theater (southeast Alabama) for the afternoon matinée — come back four/five hours later, and there I’d be, still on the front row, staring up at the screen. And thusly, I became a movie addict from the get-go.

Movies became personal. A gesture of being intimate within a crowd in a dark room, but all fixated on something else, life from another source.

An intimate cocoon of dreams. In flickering darkness, reality is made real but only in the eyes of the beholder, despite the sometimes shoulder-to-shoulder experience found in a movie theater. Movies affect/effect that beholder, producing both a change and at the same time, the sense of bringing about a desired/or undesired result.

And in the consequence, the movie-drug allowed us to set aside reality for another form of reality — imagined actuality, where being real or not doesn’t matter.

In the long, paranoid/neurotic run, maybe not such a good thing.

And movies have an eerie, long-lasting influence. A few years ago, I read Charles Isherwood’s piece of movie nostalgia in a print edition of the New York Times, which focused on the turning point, or maybe the drowning point in his life-long love/fascination with cinema — his personal-watershed film, “The Poseidon Adventure.”

Money quote:

Still, I remember being relieved when a college film teacher I admired casually mentioned his “pretaste” period, cheerfully referring to some awful movie that he had once thought a masterpiece.

My heart was eased at the notion that I was not alone: those shaming years when I’d fallen in love with the movies — the first art form I came under the spell of — and bestowed my affections so indiscriminately were not to be regretted, but acknowledged as a rite of passage.

Isherwood, film/theater critic at the NYT, is most-likely right in his assessment of movies: True, it has occurred to me since that an aborning love of movies that happened to coincide with the 1970s disaster boom might have irreparably tainted my worldview. I certainly have always lived with an anxious sense of some malign fate ever ready to pounce.

Yet in one way or another, we’ve all adapted the influence of movies into our living. And it’s a shared experience. A nice, short note on this movie experience can be found at The Dish.

Points in life seem to sometimes point off film plots or characters — such as office water-cooler talk, nuanced by dialogue off a theater screen.

In my entire life, I’ve only known just an extreme-small-handful of people not effected by movies in some form or fashion, and some not at all by its artistic offshoots and parameters. One of those was my dad — the last movie we attended together was “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” in 1977 — and not for any discernible reason, he just never really gave movies much attention.

Way-unlike his oldest boy.

And unlike Isherwood and the clout of just one movie, I was life-wise swayed by three films, set in three different eras of my life, and left great marks on my brain — each one pushed further upward the addiction level.

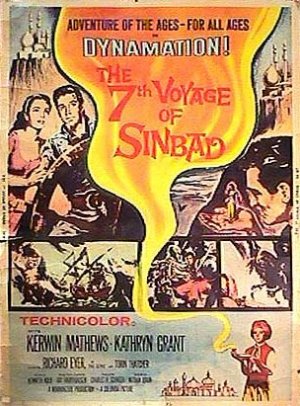

A couple of years before my book/movie epiphany, there came “The 7th Voyage of Sinbad” (1958), blowing my 10-year-old mind, which was by then a seething cauldron of an over-extended imagination.

A couple of years before my book/movie epiphany, there came “The 7th Voyage of Sinbad” (1958), blowing my 10-year-old mind, which was by then a seething cauldron of an over-extended imagination.

The plot old as shit — beautiful princess rescued by handsome prince, with evil sorcerers, and huge, delightful creatures playing along in between.

The romance was secondary compared to Ray Harryhausen’s cyclops. ‘Sinbad’ was Harryhausen’s first color movie, taking his stop-animation process to a way-new plateau of fantasy come-alive. Action-adventure afterwards was never the same. A review at Rotten Tomatoes: Films like this kick modern CGI adventure films in the nuts and then urinate on the back of their heads as they are bent double in pain.

Plus, the movie was played Saturday afternoon, the theater crammed with classmates, and was the talk at my third-grade water fountain on Monday.

(Illustration found here).

Time is so far back there, I can’t remember if I saw it again on its original run. It was a habit of mine to repeat viewings of movies I like — confounded my daddy even more — as I grew, and started going to movies during the week, not just on those silly-childish, Saturday-afternoon matinees.

Other movies during this period — such the likes of maybe “Spartacus,” or “Ben Hur,” but most were Disney, or children’s movies, like “Swiss Family Robinson,” “101 Dalmatians,” or “Pollyanna” (1960), or “In Search of the Castaways“(1962) — developed a real-bad crush on Hayley Mills, even still into her later stages, like in “Twisted Nerve” (1968), and maybe due to my kids, her stint way-later on TV’s “Saved By the Bell.”

Sprinkled among the kid flicks, were the likes also of “Ride the High Country” (1962), “To Kill a Mockingbird” (1962), “Hud” (1963), “Fail Safe” (1964), “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad World” (1963), and some adult-featured, like “Dr No” (1964).

And into this scenario came the second movie that importantly-whacked me.

In the ninth-grade, already an introverted, nerd-like kid, came adventure I didn’t know I’d been seeking.

My dad was a longtime DOD civil servant with the USAF, and in 1963 was on a stint at an American air force base near Fukuoka, Japan — the base closed in 1964, and my dad’s two-year assignment there lasted less than a year — where like all military installations, had a movie theater. Squandered a lot of time there, and for the first time, could attend the movies by myself.

My dad was a longtime DOD civil servant with the USAF, and in 1963 was on a stint at an American air force base near Fukuoka, Japan — the base closed in 1964, and my dad’s two-year assignment there lasted less than a year — where like all military installations, had a movie theater. Squandered a lot of time there, and for the first time, could attend the movies by myself.

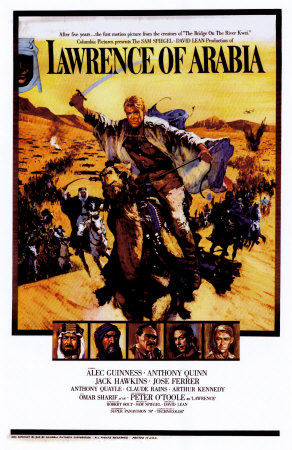

In that theater came “Lawrence of Arabia” (1962), some time after its original release, but a first for me — and was imaginatively knocked for a camel-loaded loop.

Deserts are seemingly poetic, huge and shifting and alive with a dry, curling wind — seen at a distance, even way-more so, and possessing great mystery. Rare, too, without the hint of a damsel/princess in distress within a thousand leagues.

Base theaters usually screened a movie about four times in one run, about two weeks — I saw “Lawrence” on all four occasions, and since the movie is set at nearly four hours, a shitload of camel-faces and isolated-desert.

(Illustration found here).

History far away came alive — always the history buff, too, “Lawrence” supplied my thirst for eras past, and war machines, and most-likely tapped into my own ‘loner‘ mystique-of-self — coincided with a more inward, withdrawn personality as I got older.

Even attempted Lawrence’s war-experience tome, “Seven Pillars of Wisdom,” but plodded along, nor really comprehending, and eventually left it alone. Advanced further with “Revolt in the Desert (Recollections of the Great War),” Lawrence’s later abridged version of ‘Seven Pillars,’ but still out of my league, or maybe interest.

However, I did read and highly-enjoy, “With Lawrence in Arabia,” by scholar/writer/journalist Lowell Thomas, which was the basis for the movie.

Years the movie seared into my mostly-subconscious, an onenss (if there’s such a thing), an ‘alone‘ perspective, the origin-story of my ‘loner‘ personality trait. Although I’d probably been born with that characteristic, which benefited from a shitload of other maladies, this early-to-mid-1960s period brought the attitude to fruition — ‘Wawrance‘ just quickened the path.

However, the solitary life can’t work unless apparently one likes it (or you’d be a sad, depressed person, all the time). In that sense, I’m very rarely actually ‘lonely;’ I miss people, of course, but being alone don’t hurt, and, too, I’ve never-much been ‘bored.’ The real-problem in this particular human feature of loner is the raising of children — despite not wanting to, there still occurs an arms-length mentally which sometimes can run contrary to being being a good parent.

Offset to that weirdness is to have neat, understanding kids.

Anyway, movies are beyond just something to watch — all of us cinephiles (not my favorite term for movie lovers) seek out film for interest, for reaching to the farther side.

Elizabeth Picciuto has a really-great piece on this aspect at the Daily Beast from June 2014 (as I said, this post has been around), and emotion felt at the movies — important point:

Mary Beth Oliver, a professor of media studies at Penn State, has run studies (see here and here) that suggest that people do not only watch films for pleasure.

They also watch films for insight, enlightenment, and meaningfulness.

In fact, multiple studies have shown that people think the sadder a tragedy is, the better a movie it is.

Glancing over a list of the Academy Awards Best Picture winners, there are many more thoroughly depressing movies than goofy fun rom-coms.

There’s nothing all that contrary to human nature, then, about wanting to watch a weepie.

Or soul-searching, brain-coloring.

And last in the trio of my major-influential movies is also the heaviest hitting, longest lasting, and became the last film to have any serious effect/affect on me to any degree — even now 50 years later.

And last in the trio of my major-influential movies is also the heaviest hitting, longest lasting, and became the last film to have any serious effect/affect on me to any degree — even now 50 years later.

Yet it was brain-coloring.

In 1967, I was a senior in high school, voted ‘class poet‘ for my graduating class — a girl in the drama club read my ‘class‘ poem at the Senior Breakfast (class musician had also penned a song).

I can’t remember anything about the poem, other than its goofy-title, ‘Buttercups and Green Lemonade,’ but there was much weeping due to the drama (a cheerleader gave me a kiss on the cheek with tears in her eyes, an action which seemed to make me 10-foot tall. Years later, I figured that event was my so-called 15-minutes of fame).

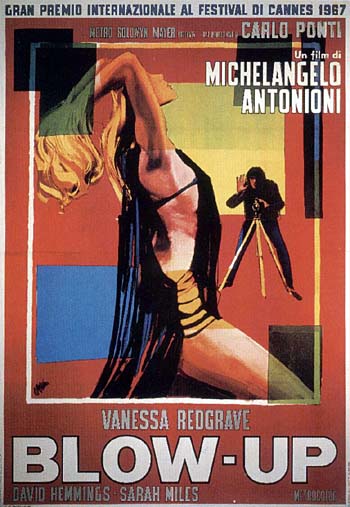

Already set-up, a movie as poem came into my view — “Blow-Up” (1966), Italian Michelangelo Antonioni’s first English-language flick.

(Illustration (blow-up) found here).

Due to my situation, I’d never been exposed to the ‘art film,’ or in general, foreign movies. Just all I remember are mainstream movies, not much in the way of Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, or Antonioni. Afterward, though, I sought such movies (and not many ‘art houses‘ in the south outside the big cities).

Sounds and colors with a mixed blend of pictures free-flowing like a free-verse poem, yet telling a tale.

And for me, ‘Blow-Up‘ came across as a metaphorical thesis for life in the mid-to-toward-the-end of the 1960s, where London was center of the universe — it’s a moving piece of artwork, like a painting animated, focusing on a day or so in the life of a photographer, despite all the glory and riches, who is sick of his shit.

Bored, and taking seemingly random photos in a park, he meets a mysterious beauty, and snaps some frames. From IMDB: ‘The fact that he may have photographed a murder does not occur to him until he studies and then blows up his negatives, uncovering details, blowing up smaller and smaller elements, and finally putting the puzzle together.’

Messed-up my brain.

I saw it twice in just a few days — took a friend the second time.

Never experienced a movie as a modern poem written on streets and sky and oddness — a desert has its poetry, but is stretched-out in history, in the past. ‘Blow-Up‘ appeared formed from an environment of swinging London, and at the exact-same time, a mystery of how live operates, producing the question: What is reality?

An excellent view of the film comes per the late-great Village Voice from July 2017, commentary based on a restoration of the film:

Because Blow-Up — even though it has had a huge influence on thrillers of all sorts, like The Conversation, Blow Out, and High Anxiety (which is, yes, a comedy, but also pretty scary) — isn’t really a mystery, nor is it really about a photographer.

…

Antonioni probably spends more time in photo shoots — capturing the surreal postures and gestures and outfits of the subjects — than he does with that central murder narrative. And to the extent that Thomas comes through at all as a character, the protagonist himself is a bit of a manipulative shit, bedding and abandoning women left and right. He’s the kind of guy who might kiss a subject in the middle of a shoot.

…

It’s a glimpse of the eternal and elemental — the dead body and the gun are both in the bushes, almost like a natural fact — that completely reorders, or rather disorders, Thomas’s world.

As an artist, he can’t capture it or understand it or do anything with it.

As an individual, he can’t possess it or consume it.

…

The film was celebrated for capturing the Sixties London scene, but there’s nothing particularly realistic or exciting about the world it depicts: The streets are often empty and quiet, and for all the flailing and groping and gyrating that happens at the shoots, concerts, and orgies, Blow-Up often feels like it’s verging into abstraction.

What Thomas’s photography ultimately “reveals” is a kind of inexpressible meaninglessness — the idea that nothing in this life makes sense, and that the closer we get to what we think is the truth, the less clear everything becomes.

And then a bunch of mimes play a fake tennis match.

And when they lose their “ball,” Thomas retrieves it for them and tosses it back.

Because why the hell not?

Whoa…reality, and the main character a nasty, caddish asshole.

A review by Roger Ebert, also from a 1998 film-festival retrospect, came to the conclusion in the reality of the nowadays:

There were of course obvious reasons for the film’s great initial success.

It became notorious for the orgy scene involving the groupies; it was whispered that one could actually see pubic hair (this was only seven years after similar breathless rumors about Janet Leigh’s breasts in “Psycho” (1960)).

The decadent milieu was enormously attractive at the time.

Parts of the film have flip-flopped in meaning.

Much was made of the nudity in 1967, but the photographer’s cruelty toward his models was not commented on; today, the sex seems tame, and what makes the audience gasp is the hero’s contempt for women.

Reality in 2018 is warped as shit, from ‘fake news,’ to conspiracy theories — study on the problem of movies and truth in a review of, Flicker: Your Brain on Movies, by Jeffrey Zacks, found at Pacific Standard magazine from November 2014.

Main point:

Why do people have such trouble distinguishing fact and fiction?

The answer, Zacks argues, is that our brains are model-building machines.

“The hard-core version of the model-building account,” he explains, “says that when we understand a story just by reading it, we fire off the same neural systems that we use to build models of the real world.”

Zacks tried to validate this model by using fMRI scanning while people watched films—and what he discovered was that when, for example, a character on screen reaches for an object, the fMRI showed activity in the area corresponding to motor hand control.

Because of these and related experiments, Zacks is convinced that “memories of our lives and memories of stories have the same shape because they are formed by the same mechanisms.”

He concludes: “It is not the case that you have one bucket into which you drop all the real-life events, another for movie events, and a third for events in novels.”

Your model-building brain “is perfectly happy to operate on stuff from your life, from a movie, or from a book.”

That’s “a big part of the appeal of narrative films and books,” Zacks argues.

“[T]hey appeal to our model-building propensities.”

But it’s also why we have trouble separating out what’s real and what’s fiction.

Human brains use models to understand reality, and it doesn’t matter whether the model is labeled “fiction” or “fact.”

In the age of awesome liar, the T-Rump, movies can’t distinguish phony from real…

(Illustration out front found here).