Sunshine and warm temps this late afternoon Friday in California’s Central Valley — another most-gorgeous day.

In the opposite direction, another spin here into the upcoming 20th anniversary of the invasion of Iraq — on Monday marks the shit point where a lot of ugly history started, and the repercussions continue right into the right now. Except there was a lot of bravery included in the mix..

At the beginning of the war, the invasion was miscalculated like all the rest — one reporter’s perspective:

What one @washingtonpost colleague witnessed on the Army's "thunder run" to Baghdad 20 years agohttps://t.co/7VuiSY9KRs

— Dan Lamothe (@DanLamothe) March 17, 2023

The ‘colleague,’ William Branigin, in his piece at The Washington Post this morning, does describe an awful and scary run into the shock and awe, the initial “thunder run,” of the beginnings to the war, a first-person account of some horrific shit — some snips:

Twenty years ago, as a Washington Post reporter embedded with the 3rd Infantry Division, I watched the battle for Objective Curly unfold from an M88 armored recovery vehicle positioned under an overpass that carried the Dawrah Expressway over Highway 8.

The fighting steadily intensified as Hussein loyalists converged on the interchange. By the afternoon, the American tanks and Bradleys farther north began to run low on fuel and ammunition.

The mission to capture the capital and topple the Iraqi dictator hung in the balance.

This is the story of the invasion mainly as experienced by the unit I accompanied on the drive to Baghdad — Bravo Company of the 3rd Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment (a.k.a. Task Force 3-15), of the 3rd ID’s 2nd Brigade. The division brought a storied record to the campaign. Its 15th Regiment spent 26 years in China in the early 1900s, giving TF 3-15 its nickname, the China Battalion.

Roughly 600 reporters covered the invasion as “embeds” with various military units, and a few hundred more, dubbed “unilaterals,” moved around independently. At least 16 from both groups died, four of them embedded with the 3rd Infantry Division. They included Michael Kelly, 46, an Atlantic magazine editor and Post columnist, and David Bloom, 39, an NBC correspondent.

The M88 was used mainly for towing and repairing tanks and Bradleys. But the 56-ton behemoth sat higher than other vehicles, and I had access to the rear hatch, enabling me to write stories on the move and transmit them by sticking the magnetic antenna of my Iridium satellite phone onto the armor on top.

[…]

But the U.S. soldiers’ heroic actions — as well as the sheer military accomplishment of the invasion that culminated in the stunning thrust into Baghdad — were soon overshadowed, at least in the public’s eye, by popular revulsion toward a war that eventually claimed the lives of more than 4,500 Americans and at least 186,000 Iraqi civilians.

Despite an intensive search, the United States never found the purported “weapons of mass destruction” that formed President George W. Bush’s main rationale for invading. And his administration’s failure to plan for and properly implement the occupation phase of the campaign contributed to the growth of an insurgency that ensnared U.S. troops and inflicted casualties long after combat was supposed to be over. Another rationale, deposing a brutal dictator, also came to be viewed as insufficient justification for going to war.

“The thunder run was an example of what happens when the leadership is really good,” said Peter Kilner, an ethics instructor at the U.S. Military Academy who participated in an Army study of the invasion. The downside was that “the rest of the Army was totally unprepared for the fall of Baghdad.” It happened so fast that “we caught ourselves off guard.” As the occupation foundered and the insurgency grew, he said, “people weren’t proud of the war,” making it harder for the public to celebrate the troops’ achievements.

For the soldiers involved in the thunder run, however, “that point never comes up,” said Perkins, who retired in 2018 as a four-star general. “What they really focus on is the accomplishment of that day. And they focus on the courage and heroism of their fellow soldiers.”

If you can, go check out the whole piece — reads like a war novel, but one where you feel, and know the end.

Further in that way-badly thought-out adventure: In a piece published this afternoon at the Guardian by Martin Chulov has a quick snip on the overall real-time flow to the all-encompassing Iraqi clusterf*ck. Chulov, who covers the Middle East for the Guardian, was awarded the aptly titled Orwell prize for journalism in 2015. He anchors this particular piece on the shift for/against the war — no suspicion of the consequences in hundreds of thousands of lives, the horror of ISIS, among a huge, massive shitload of ramifications:

It was not always that way. As a young US marine sergeant dispatched to Kuwait for the invasion, Ken Griffin had been itching to make a positive difference.

“When we began our march to Baghdad, I was 100 percent certain we were there for the right reasons,” he says. “When you’re a young marine, it’s unfathomable that the government would lie to you. Or send you to war when it didn’t have to. When you’re in that situation and find yourself in battle, you aren’t hindered by the little things like: “Should we be here?” or “Is that just?” – you know in all your heart that it’s the right thing to do.

“When you see columns of Iraqi soldiers gladly surrendering in exchange for food and shelter, it reinforces that belief. When men, women and children are smiling and waving at your column, you know all you need to know.

“Later, when Iraqis attack you under the cover of darkness, you don’t think it might be the same people who were smiling and waving. These are bad actors, evil people. The ones you came to get rid of. The fact that they could be the same people who smiled and waved: that’s a cynical realisation you won’t be ready for until years later.”

Iraqis greeting American forces as liberators, then fighting them as occupiers, became a reality for troops who had helped topple Saddam and then stayed on, ostensibly to help rebuild the country. By late 2003, George W Bush’s belief that Iraq could be transformed into a democracy at the heart of the Middle East was looking ill-conceived. Within three years, it had become a bloody delusion that had killed several thousand US troops, more than 100,000 Iraqis, and caused the country to spiral into an abyss.

The young marine 20 years later:

Griffin remains troubled by his time in Iraq. “When people would die, even though they were strangers, it affected me deeply. As a young marine I could look people in the eye and say they died fighting for their country.

“At some point I lost that and just saw the deaths as profound wastes of life. One would assume I’m just talking about friends, or Americans, but I grieved for the massive amount of civilians who were often randomly plucked off the Earth – only guilty of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Many of them are just struggling to live their lives or maintain some normalcy by having dinner along the Tigris River or keeping their children in school.”

Another good Guardian piece today on the Iraqi debacle concerns movies on the invasion, occupation, the side effects, and other aspects of that now-horror of history — from “The Hurt Locker,” “W,” “Vice,” to “American Sniper,” and on — an interesting view of cinematic takes on the subject. Supposedly, though, not very popular with moviegoers

And a not-shocking and aweing moment of a GW Bush last year guilt-speaking the ass-front of Ukraine:

Despite a couple of decades, here we are once again…

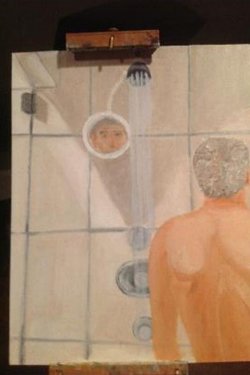

(Illustration out front: A self-portrait artwork by GW Bush, and found here.)

(Illustration out front: A self-portrait artwork by GW Bush, and found here.)