Sunshine earlier this afternoon, and now a pleasant Saturday evening in California’s Central Valley, this another post tagging along with one earlier today on the ill business of climate change — Rod Serling strolling the deck of the Titanic with full foreknowledge of what’s going to happen, ‘submitted for your approval,’ the horror to come.

Noteworthy:

Being a climate scientist sometimes feels like being an astrophysicist in one of those 90s asteroid impact disaster movies…

except instead of coming to together to save humanity, the people in power shrug & point out how sending rockets might increase inflation. #ClimateChange https://t.co/PJzfQSYsbx— Daniel Swain (@Weather_West) November 17, 2021

Read a review of the movie, “Don’t Look Up,” if you want, at Foreign Policy from this morning and it’s not good, though, supposedly .climate folks like it, here and here.

Meanwhile, some real climate change reality impacts, in this particular case, snowless winters in the western mountains, and soon, too — from Wired this morning:

Across the Central Rockies, it’s been an unseasonably warm, dry year. Denver smashed the record for its latest first measurable winter snow. Colorado ski resorts delayed opening because temperatures were too high to even produce fake snow. And Salt Lake City was entirely snowless through November, for only the second time since 1976.

These snowless scenarios, while still an exception, are set to become much more common as early as 2040, according to a paper published in Nature Reviews Earth and Environment. Drawing from years of snowpack observations, the researchers project that, in 35 to 60 years, the Mountain West will be nearly snowless for years at a time if worldwide greenhouse gas emissions are not rapidly reduced. This could impact everything from wildfires to drinking water.

…

The effects will extend far beyond just shuttered ski resorts. The study points out that the declining snowpack is already contributing to another growing problem in the West: extreme wildfires. Lack of snow after wildfires could make it much harder for forests to recover.

“Snow matters after the fire in terms of facilitating or fostering the revegetation of the area,” said Anne Nolin, a snow hydrologist and professor at the University of Nevada, Reno, who has studied the connection between snow and post-wildfire forest recovery. (Nolin was not involved with the paper.)

And with more precipitation falling as rain instead of snow, this could permanently alter the kind of vegetation that grows back, as well as the structure of the soils, which can lead to issues like erosion.

“This all has cascading impacts,” Nolin said.But perhaps the biggest impact will be on water supply. About 75-percent of the water used in the Western US comes from snowmelt. The Colorado River, for example, is fed by mountain snow and supplies drinking water for more than 40 million people.

Western rivers also generate electricity and provide irrigation for millions of acres of farmland.

“Every state in the West that is dry or uses Colorado River water is being impacted,” said Nolin. That includes Lake Mead, which is fed by the Colorado.

Nolin recently flew over the reservoir and was shocked by how low it was. Water lines on the rock, staining the rocks white, were visible several feet above the actual water surface.

And my home-zone calls for a mention: ‘Other dry areas, like California’s San Joaquin Valley, are already facing a water crisis brought about by drought and shrinking aquifers. With the snowpack receding, drought lingering, and the groundwater getting sucked up by agriculture, several communities have already lost all access to their drinking water.‘

Another anxiety-influenced item on the endless list of worrisome shit.

And finally, just to rub it into the mud-face of climate reality, here’s an addition to my post this morning on how environmental studies are always having to shift direction when shit actually becomes worse than some report or another indicated previously, another example of how much climate change research can be low-balled

A look at climate change’s impact on certain agricultural products, published earlier this month at Nature as once again shit’s worse than we first figured — from the Abstract:

Here we report new twenty-first-century projections using ensembles of latest-generation crop and climate models. Results suggest markedly more pessimistic yield responses for maize, soybean and rice compared to the original ensemble.

…

The ‘emergence’ of climate impacts consistently occurs earlier in the new projections—before 2040 for several main producing regions.

While future yield estimates remain uncertain, these results suggest that major breadbasket regions will face distinct anthropogenic climatic risks sooner than previously anticipated.

And onward.

However here we are, once again…

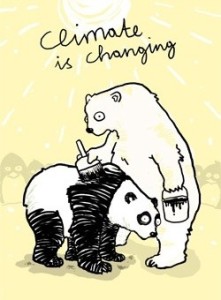

(Illustration out front by Handoko Tjung, found here)

(Illustration out front by Handoko Tjung, found here)