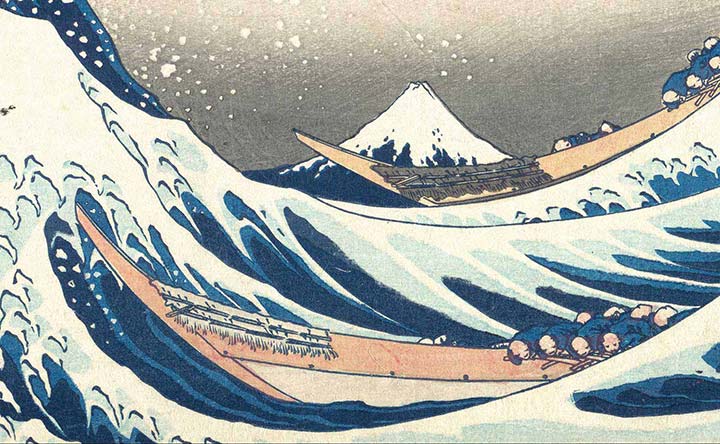

(Illustration: Woodblock print by the Japanese ukiyo-e artist Hokusai, ‘The Great Wave,’ found here).

(Illustration: Woodblock print by the Japanese ukiyo-e artist Hokusai, ‘The Great Wave,’ found here).

In human behavior it seems, accepting belief in a nut-job conspiracy theory and handling COVID-19 misinformation are two distinct dumb-ass positions. This for sure has been an era of conspiracy theories, pop-up delusions and deceptions galore, but with the virus it can be immediately fatal.

Relative to that, here’s a quick a look at research into both, and the consequences.

A recent study looked at both schemes of evil and bad particulars about COVID and how they each prevail — a review of the research was published this past November at Havard Library — some high points of the summary (pdf):

Using a national survey of U.S. adults fielded June 4–17, 2020 (n = 1,040), we found that conspiracy theories, especially those promoted by visible partisan figures, exhibited higher levels of support than medical misinformation about the treatment and transmissibility of COVID-19.

This suggests that potentially dangerous health misinformation is more difficult to believe than abstract ideas about the nefarious intentions of governmental and political actors.

…

While some dubious beliefs find roots in liberal-conservative ideology and support for President Trump, belief in health-related misinformation is more a product of distrust in scientists.

…

The first implication of our findings is that some dubious ideas find more support than others and may, therefore, matter more.

For example, the theory that “the number of deaths related to the coronavirus has been exaggerated” is endorsed by nearly 30-percent of Americans, compared to only 13-percent who believe that “Bill Gates is behind the coronavirus pandemic.”

More abstract conspiracy theories tend to find the most support, likely because of their greater generality…The more general the dubious idea, the easier it is for individuals to fill in specific details using their existing belief system and other predispositions.

T-Rump enters the picture:

More specific misinformation about the treatment and transmissibility of COVID-19, in contrast, finds less support. For example, only 12-percent of respondents agree that “putting disinfectant into your body can prevent or cure COVID-19.”

While policymakers and public health officials should be concerned that anyone believes this, the relatively meager support signals, on the one hand, the general public’s resilience to some dangerous misinformation, even when it is spread by the president.

…

In our analyses, Trump support and conservative self-identification are associated with several conspiracy theories and health-related misinformation precisely because Trump and his allies engage in conspiracy theorizing and misinformation.

Maybe now a shift in mask wearing and social distancing.

Yet another study in COVID behavior found it depends on your life-bubble — close friends, family. From the UK’s University of Nottingham University News last Thursday:

New research has shown that people are more likely to follow Covid-19 restrictions based on what their friends do, rather than their own principles.

Research led by the University of Nottingham carried out in partnership with experts in collective behaviour from British, French, German and American universities shows how social influence affects people’s adherance to government restrictions.

The researchers found that the best predictor of people’s compliance to the rules was how much their close circle complied with the rules, which had an even stronger effect than people’s own approval of the rules.The research published in British Journal of Psychology highlights a blindspot in policy responses to the pandemic. It also suggests that including experts in human and social behaviour is crucial when planning the next stages of the pandemic response, such as how to ensure that people comply with extended lockdowns or vaccination recommendations.

Lead researcher, Dr Bahar Tunçgenç University of Nottingham’s School of Psychology, and a research affiliate at the University of Oxford:

“When coronavirus first hit the UK in March, I was struck by how differently the leaders in Europe and Asia were responding to the pandemic. While the West emphasised ‘each person doing the right thing’, pandemic strategies in countries like Singapore, China and South Korea focussed on moving the collective together as a single unit…

“There is much that human behaviour research can offer to implement effective policies for the Covid-19 challenges we will continue to face in the future…

Using social media to demonstrate to your friends that you are following the rules, rather than expressing outrage at people who aren’t following them could also be a more impactful approach.

At national and local levels, public messages by trusted figures can emphasise collective values, such as working for the benefit of our loved ones and the community. Our message to policymakers is that even when the challenge is to practise social distancing, social closeness is the solution!”

Apparently COVID misinformation spreads rapidly, like the virus, according to research from Boston University School of Public Health, Harvard Medical School and École Polytechnique Fédérale (findings published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research) — via Mint Lounge, also from last Thursday:

The researchers focused on myths that the World Health Organization (WHO) “busted” on its website.

This included relationships between covid-19 and alcohol, ginger root, the sun, 5G, and the medicine hydroxychloroquine.

The team constructed a list consisting of a combination of “Coronavirus,” “covid-19,” “covid19,” and “covid” with other misinformation terms such as ‘wine,’ ‘hot weather,’ ‘antibiotics,’ ‘chlorine,’ ‘garlic,’ ‘pepper,’ ‘houseflies,’ ‘mosquito,’ ‘hand dryer,’ ‘supplement,’ and ‘saline.’

…

According to an official news release, the team was surprised that there seemed to be a consistent, global misunderstanding of 5G technology.

The myth of “covid-19 and 5G” spread faster than any of the other rumors they investigated.

“I didn’t expect 5G to stand out among the misinformation as much as it did,” Elaine Nsoesie, a Hariri Institute Faculty Fellow and Assistant Professor in the BU School of Public Health, who led the research team said in the release.The researchers also found that “debunking” myths online seemed effective in stopping their spread — almost like how the continued use of face masks has shown to protect people from the novel coronavirus.

As soon as WHO public health officials responded to covid-19 misinformation on their website, the number of Google searches for that particular misinformation topic dropped significantly, the release explains.The research team also added that to stop the spread of similar myths in the future, experts should consistently and clearly correct common misconceptions.

They also believe the rapid proliferation of misinformation that discourages adherence to public health interventions could be predictive of future increases in disease cases.

Good idea.

And finally, a look at what a mask mandate would have accomplished early-on in the pandemic. From January’s Science Direct and the study’s Abstract:

Our main counterfactual experiments suggest that nationally mandating face masks for employees early in the pandemic could have reduced the weekly growth rate of cases and deaths by more than 10 percentage points in late April and could have led to as much as 19 to 47-percent less deaths nationally by the end of May, which roughly translates into 19 to 47 thousand saved lives.

We also find that, without stay-at-home orders, cases would have been larger by 6 to 63-percent and without business closures, cases would have been larger by 17 to 78-percent.

We find considerable uncertainty over the effects of school closures due to lack of cross-sectional variation; we could not robustly rule out either large or small effects.

Overall, substantial declines in growth rates are attributable to private behavioral response, but policies played an important role as well.

At least we’re back now with science:

Dr. Anthony Fauci says it's "liberating" to be able to "let the science speak" now in the Biden White House https://t.co/LJVeS4TmF0

— CNN (@CNN) January 21, 2021

Here we go…

(Illustration: Pablo Picasso’s ‘The Weeping Woman [La Femme qui pleure],’ found here).

(Illustration: Pablo Picasso’s ‘The Weeping Woman [La Femme qui pleure],’ found here).